Agent Builder is available now GA. Get started with an Elastic Cloud Trial, and check out the documentation for Agent Builder here.

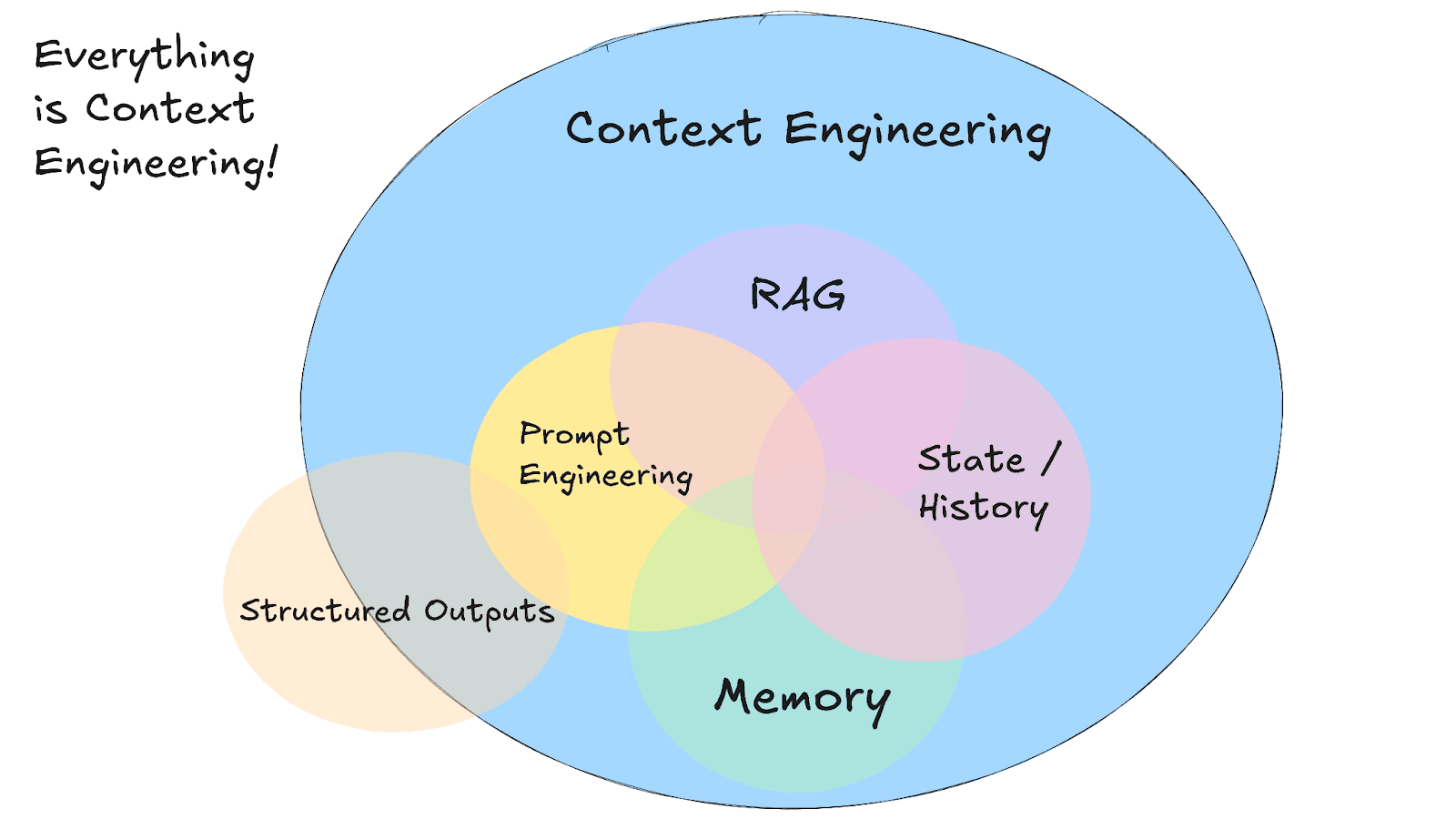

In the emerging discipline of context engineering, giving AI agents the right information at the right time is crucial. One of the most important aspects of context engineering is managing an AI’s memory. Much like humans, AI systems rely on both a short-term memory and a long-term memory to recall information. If we want large language model (LLM) agents to carry on logical conversations, remember user preferences, or build on previous results or responses, we need to equip them with effective memory mechanisms.

After all, everything in the context influences the AI’s responses. Garbage in, garbage out holds true.

In this article, we’ll introduce what short-term and long-term memory mean for AI agents, specifically:

- The difference between short- and long-term memory.

- How they relate to retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) techniques with vector databases, like Elasticsearch, and why careful memory management is necessary.

- The risks of neglecting memory, including context overflow and context poisoning.

- Best practices, like context pruning, summarizing, and retrieving only what’s relevant, to keep an agent’s memory both useful and safe.

- Finally, we’ll touch on how memory can be shared and propagated in multi-agent systems to enable agents to collaborate without confusion using Elasticsearch.

Short-term versus long-term memory in AI agents

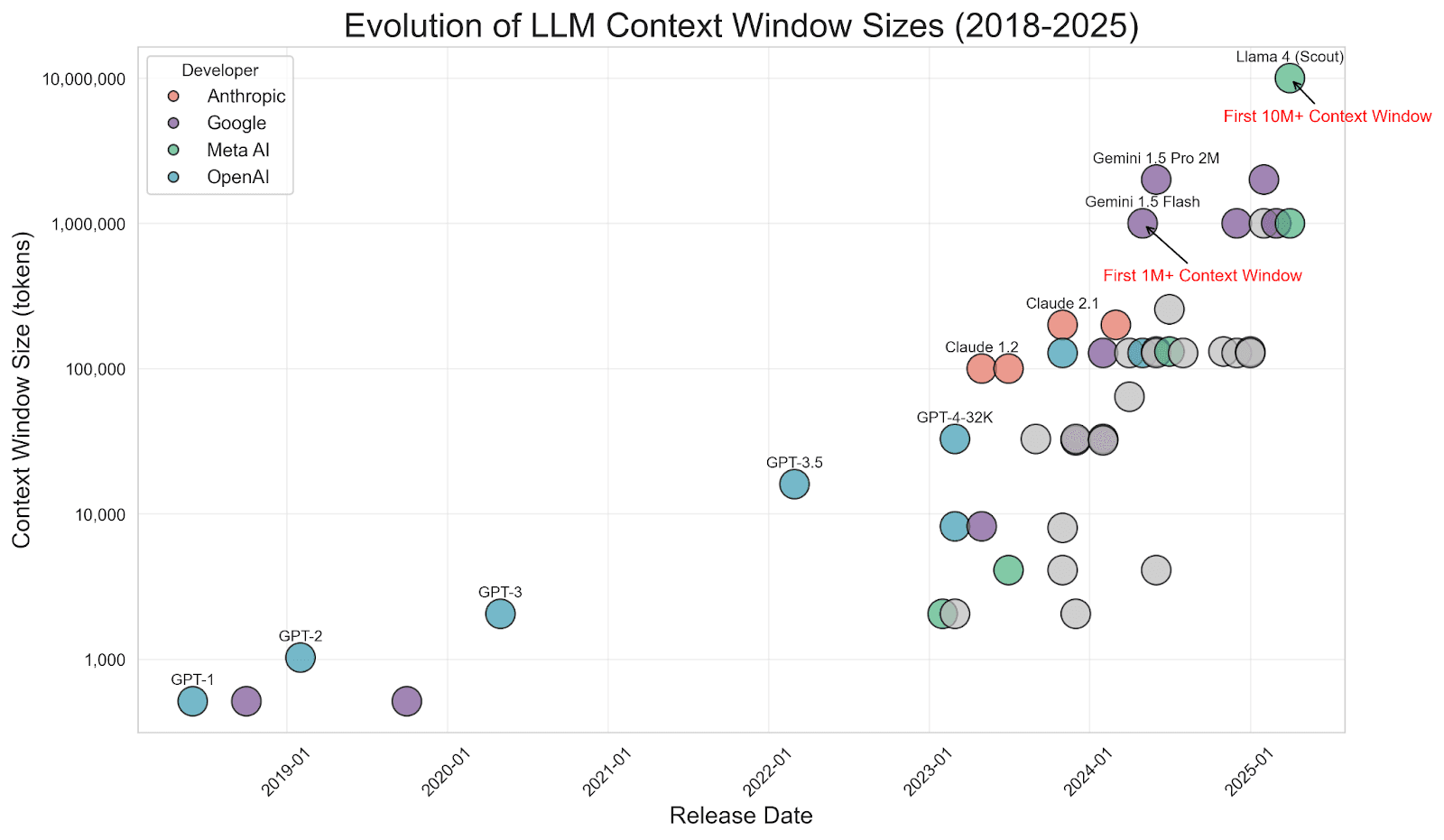

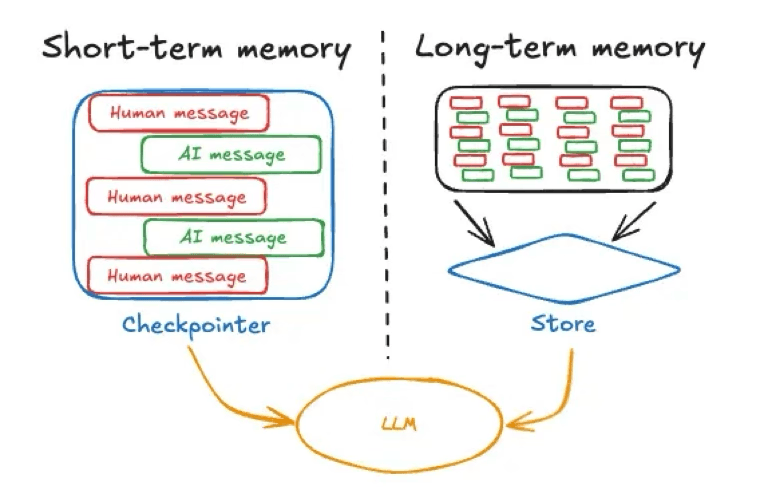

Short-term memory in an AI agent typically refers to the immediate conversational context or state—essentially, the current chat history or recent messages in the active session. This includes the user’s latest query and recent back-and-forth exchanges. It’s very similar to the information a person holds in mind during an ongoing conversation.

Image source: https://langchain.ai.github.io/langgraphjs/concepts/memory

AI frameworks often maintain this transient memory as part of the agent’s state (for example, using a checkpointer to store the conversation state as covered by this example from LangGraph). Short-term memory is session-scoped; that is, it exists within a single conversation or task and is reset or cleared when that session ends, unless explicitly saved elsewhere. An example of session-bound short-term memory would be the temporary chat available in ChatGPT.

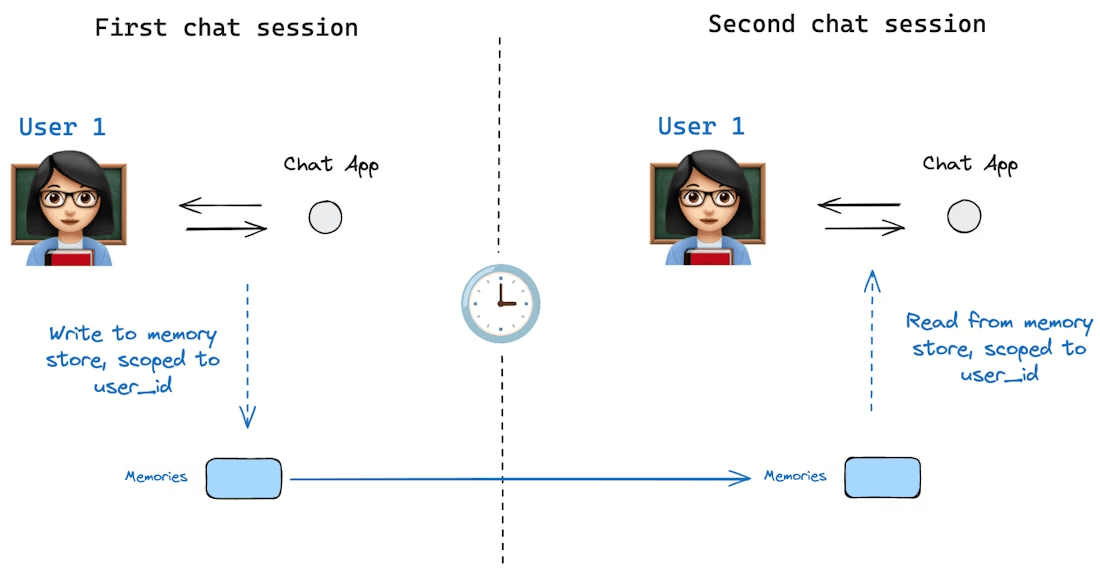

Image source: https://docs.langchain.com/oss/python/langgraph/persistence#memory-store

Long-term memory, on the other hand, refers to information that persists across conversations or sessions. This is the knowledge an agent retains over time, facts it learned earlier, user preferences, or any data we’ve told it to remember permanently.

Long-term memory is usually implemented by storing and fetching it from an external source, such as a file or vector database that’s outside the immediate context window. Unlike short-term chat history, long-term memory isn’t automatically included in every prompt. Instead, based on a given scenario, the agent must recall or retrieve it when relevant tools are invoked. In practice, long-term memory might include a user’s profile info, prior answers or analyses the agent produced, or a knowledge base the agent can query.

For instance, if you have a travel-planner agent, the short-term memory would contain details of the current trip inquiry (dates, destination, budget) and any follow-up questions in that chat; whereas the long-term memory could store the user’s general travel preferences, past itineraries, and other facts shared in previous sessions. When the user returns later, the agent can pull from this long-term store (for example, the user loves beaches and mountains, has an average budget of INR 100,000, has a bucket list to visit, and prefers to experience history and culture rather than kid-friendly attractions) so that it doesn’t treat the user as a blank slate each time.

The short-term memory (chat history) provides immediate context and continuity, while long-term memory provides a broader context that the agent can draw upon when needed. Most advanced AI agent frameworks enable both: They keep track of recent dialogue to maintain context and offer mechanisms to look up or store information in a longer-term repository. Managing short-term memory ensures it stays within the context window, while managing long-term memory helps the agent to ground the answers based on prior interactions and personas.

Memory and RAG in context engineering

Image source: https://github.com/humanlayer/12-factor-agents/blob/main/content/factor-03-own-your-context-window.md

How do we give an AI agent a useful long-term memory in practice?

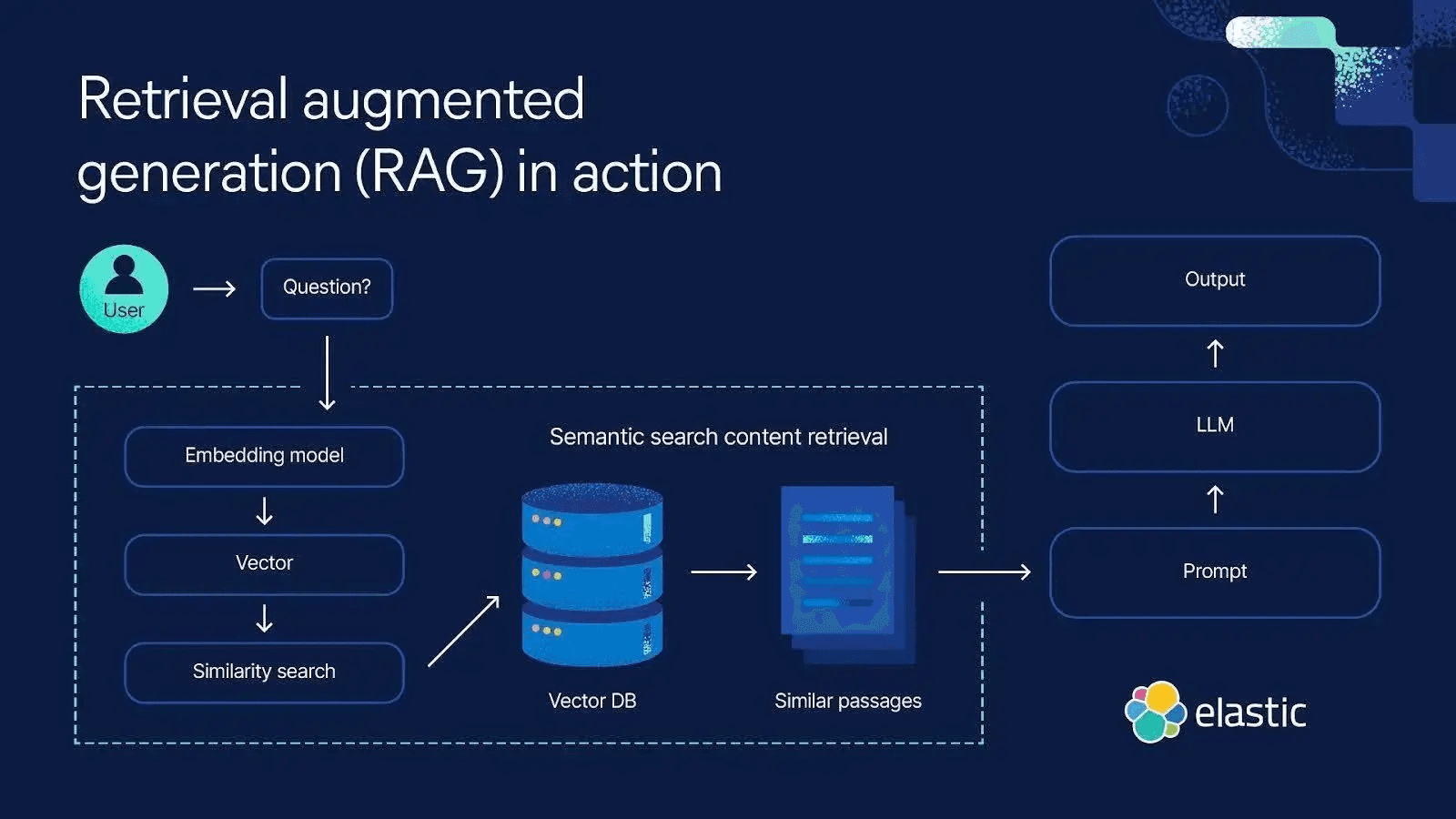

One prominent approach for long-term memory is semantic memory, often implemented via retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). This involves coupling the LLM with an external knowledge store or vector-enabled datastore, like Elasticsearch. When the LLM needs information beyond what’s in the prompt or its built-in training, it performs semantic retrieval against Elasticsearch and injects the most relevant results into the prompt as context. This way, the model’s effective context includes not only the recent conversation (short-term memory) but also pertinent long-term facts fetched on the fly. The LLM then grounds its answer on both its own reasoning and the retrieved information, effectively combining short-term memory and long-term memory to produce a more accurate, context-aware response.

Elasticsearch can be used to implement long-term memory for AI agents. Here’s a high-level example of how context can be retrieved from Elasticsearch for long-term memory.

This way, the agent “remembers” by searching for relevant data rather than by storing everything in its limited prompt, where it leads to different risks.

Using RAG with Elasticsearch or any vector stores offers multiple benefits:

First, it extends the knowledge of the model beyond its training cutoff. The agent can retrieve up-to-date information or domain-specific data that the LLM might not know. This is crucial for questions about recent events or specialized topics.

Second, retrieving context on demand helps reduce hallucinations, especially since LLMs aren’t trained on the proprietary or highly specialized data relative to your niche use case, which is highly likely to expose it to hallucinations. Instead of the LLM guessing or inventing new information as it has been incentivised through evaluation, as highlighted in a recent OpenAI paper (Why Language Models Hallucinate), the model can be grounded by factual references from Elasticsearch. Naturally, the LLM depends on the reliability of the data in the vector store to truly prevent misinformation and the relevant data is retrieved as per the core relevance measures.

Third, RAG allows an agent to work with knowledge bases far larger than anything you could ever fit into a prompt. Instead of pushing entire documents, like long research papers or policy documents, into the context window and risking overload or irrelevant information context poisoning the model’s reasoning, RAG relies on chunking. Large documents are broken into smaller, semantically meaningful pieces, and the system retrieves only the few chunks most relevant to the query. This way, the model doesn’t need a million-token context to appear knowledgeable; it just needs access to the right chunks of a much larger corpus.

It’s worth noting that as LLM context windows have grown (some models now support hundreds of thousands or even millions of tokens), a debate arose about whether RAG is “dead.” Why not push all the data into the prompt? If you feel likewise, refer to this wonderful article by my colleagues, Jeffrey Rengifo and Eduard Martin, Longer context ≠ better: Why RAG still matters. This avoids the “garbage in, garbage out” problem: The LLM stays focused on the few chunks that matter, rather than running through noise.

That said, integrating Elasticsearch or any vector store into an AI agent architecture provides long-term memory. The agent stores knowledge externally and pulls it in as memory context when needed. This could be implemented as an architecture, where after each user query, the agent performs a search on Elasticsearch for relevant info and then appends the top results to the prompt before calling the LLM. The response might also be saved back into the long-term store if it contains useful new information (creating a feedback loop of learning). By using such retrieval-based memory, the agent remains informed and up to date, without having to cram everything it knows into every prompt, even though the context window supports one million tokens. This technique is a cornerstone of context engineering, combining the strengths of information retrieval and generative AI.

Here’s an example of a managed in-memory conversation state using LangGraph's checkpoint system for short-term memory during the session. (Refer to our supporting context engineering app.)

Here’s how it stores checkpoints:

For long-term memory, here's how we perform semantic search on Elasticsearch to retrieve relevant previous conversations using vector embeddings after summarizing and indexing the checkpoints to Elasticsearch.

Now that we’ve explored how short-term memory and long-term memory are indexed and fetched using LangGraph’s checkpoints in Elasticsearch, let’s take some time to understand why indexing and dumping the complete conversations can be risky.

Risks of not managing context memory

As we’re talking much about context engineering, along with short-term and long-term memory, let’s understand what happens if we don’t manage an agent’s memory and context well.

Unfortunately, many things can go wrong when an AI’s context grows extremely long or contains bad information. As context windows get larger, new failure modes emerge, like:

- Context poisoning

- Context distraction

- Context confusion

- Context clash

- Context leakage and knowledge conflicts

- Hallucinations and misinformation

Let’s break down these issues and other risks that arise from poor context management:

Context poisoning

Context poisoning refers to when incorrect or harmful information ends up in the context and “poisons” the model’s subsequent outputs. A common example is a hallucination by the model that gets treated as fact and inserted into the conversation history. The model might then build on that error in later responses, compounding the mistake. In iterative agent loops, once a false information makes it into the shared context (for example, in a summary of the agent’s working notes), it can be reinforced over and over.

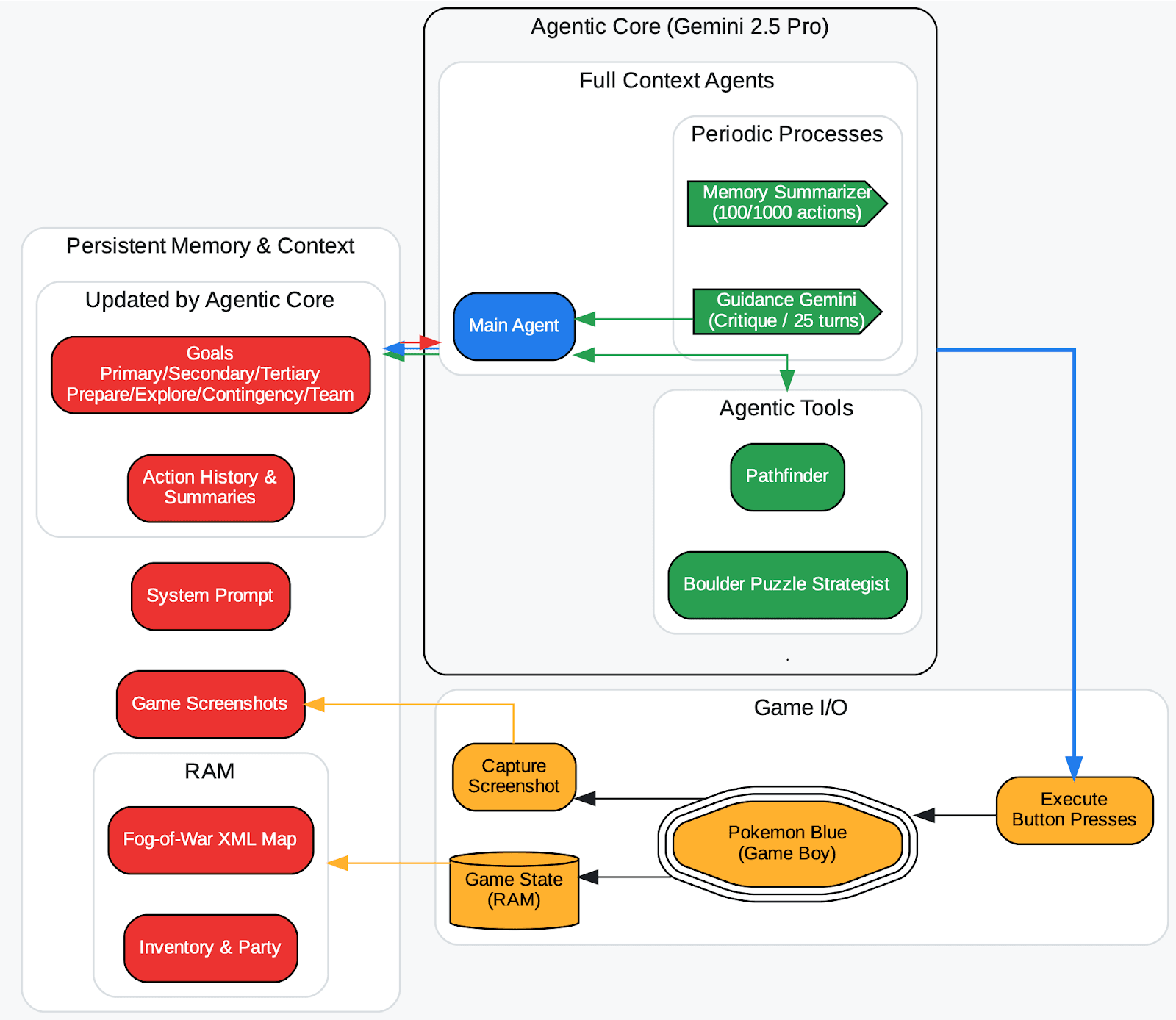

Researchers at DeepMind, in the release of the Gemini 2.5 report (TL;DR, check here), observed this in a long-running Pokémon-playing agent: If the agent hallucinated a wrong game state and that got recorded into its context (its memory of goals), the agent would form nonsensical strategies around an impossible goal and get stuck. In other words, a poisoned memory can send the agent down the wrong path indefinitely.

An overview of the agent harness (Zhang, 2025). The overworld fog-of-war map automatically stores a tile once explored and labels it with a visited counter. The type of tile is recorded from RAM. The agentic tools (pathfinder, boulder_puzzle_strategist) are prompted instances of Gemini 2.5 Pro. pathfinder is used for navigation and boulder_puzzle_strategist solves boulder puzzles in the Victory Road dungeon.

Image source: https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/gemini/gemini_v2_5_report.pdf - page68.

Context poisoning can happen innocently (by mistake) or even maliciously, for instance, via prompt injection attacks where a user or third-party sneaks in a hidden instruction or false fact that the agent then remembers and follows.

Recommended countermeasures:

Based on insights from Wiz, Zerlo, and Anthropic, countermeasures for context poisoning focus on preventing bad or misleading information from entering an LLM’s prompt, context window, or retrieval pipeline. Key steps include:

- Check the context constantly: Monitor the conversation or retrieved text for anything suspicious or harmful, not just the starting prompt.

- Use trusted sources: Score or label documents based on credibility so the system prefers reliable information and ignores low scored data.

- Spot unusual data: Use tools that detect odd, out-of-place, or manipulated content, and remove it before the model uses it.

- Filter inputs and outputs: Add guardrails so harmful or misleading text can’t easily enter the system or be repeated by the model.

- Keep the model updated with clean data: Regularly refresh the system with verified information to counter any bad data that slipped through.

- Human-in-the-loop: Have people review important outputs or compare them against known, trustworthy sources.

Simple user habits also help, resetting long chats, sharing only relevant information, breaking complex tasks into smaller steps, and maintaining clean notes outside the model.

Together, these measures create a layered defense that protects LLMs from context poisoning and keeps outputs accurate and trustworthy.

Without countermeasures as mentioned here, an agent might remember instructions, like ignore previous guidelines or trivial facts that an attacker inserted, leading to harmful outputs.

Context distraction

Context distraction is when a context grows so long that the model overfocuses on the context, neglecting what it learned during training. In extreme cases, this resembles catastrophic forgetting; that is, the model effectively “forgets” its underlying knowledge and becomes overly attached to the information placed in front of it. Previous studies have shown that LLMs often lose focus when the prompt is extremely long.

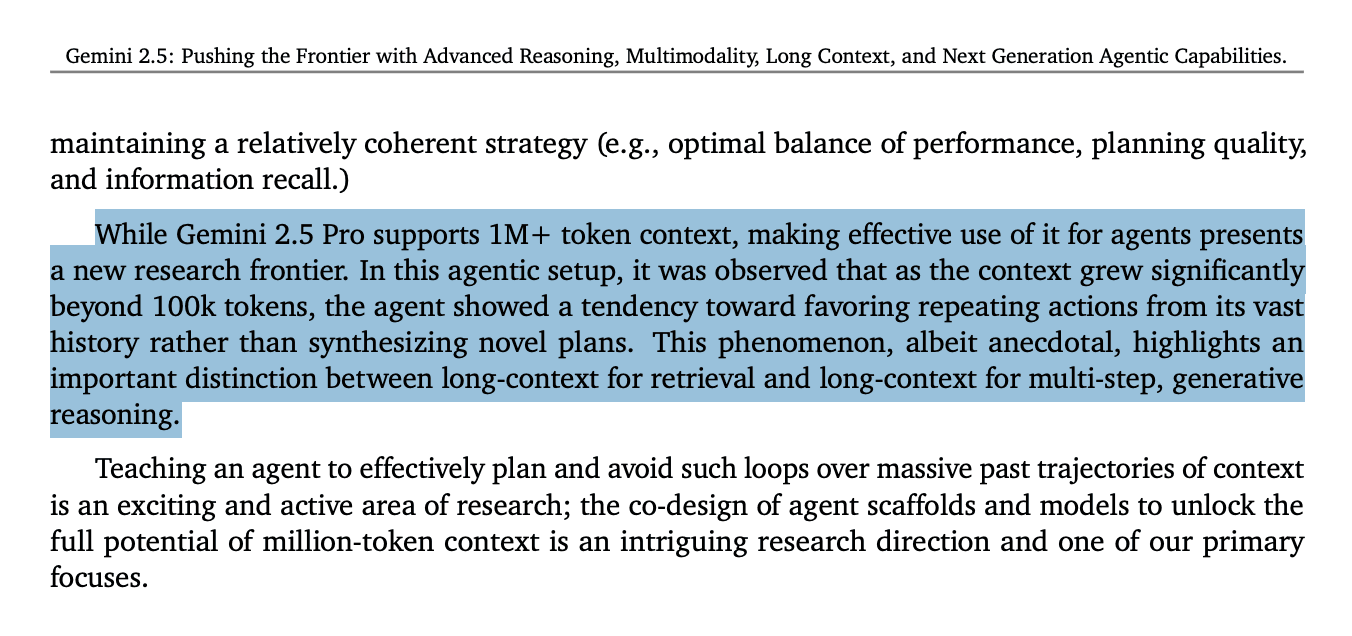

The Gemini 2.5 agent, for example, supported a million-token window, but once its context grew beyond a certain point (on the order of 100,000 tokens in an experiment), it began to fixate on repeating its past actions instead of coming up with new solutions. In a sense, the agent became a prisoner of its extensive history. It kept looking at its long log of previous moves (the context) and mimicking them, rather than using its underlying training knowledge to devise fresh and novel strategies.

Image source: https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/gemini/gemini_v2_5_report.pdf - page18.

This is counterproductive. We want the model to use relevant context to help reasoning, not override its ability to think. Notably, even models with huge windows exhibit this context rot: Their performance degrades nonuniformly as more tokens are added. There appears to be an attention budget., Like humans with limited working memory, an LLM has a finite capacity to attend to tokens, and as that budget is stretched, its precision and focus drop.

As a mitigation, you can prevent context distraction using chunking, engineering the right information, regular context summarization, and evaluation and monitoring techniques to measure the accuracy of the response using scoring.

These methods keep the model grounded in both relevant context and its underlying training, reducing the risk of distraction and improving overall reasoning quality.

Context confusion

Context confusion is when superfluous content in the context is used by the model to generate a low-quality response.A prime example is giving an agent a large set of tools or API definitions that it might use. If many of those tools are unrelated to the current task, the model may still try to use them inappropriately, simply because they’re present in context. Experiments have found that providing more tools or documents can hurt performance if they’re not all needed. The agent starts making mistakes, like calling the wrong function or referencing irrelevant text.

In one case, a small Llama 3.1 8B model failed a task when given 46 tools to consider but succeeded when given only 19 tools. The extra tools created confusion, even though the context was within length limits. The underlying issue is that any information in the prompt will be attended to by the model. If it doesn’t know to ignore something, that something could influence its output in undesired ways. Irrelevant bits can “steal” some of the model’s attention and lead it astray (for instance, an irrelevant document might cause the agent to answer a different question than asked). Context confusion often manifests as the model producing a low-quality response that integrates unrelated context. Refer to the research paper: Less is More: Optimizing Function Calling for LLM Execution on Edge Devices.

It reminds us that more context isn’t always better, especially if it’s not curated for relevance.

Context clash

Context clash occurs when parts of the context contradict each other, causing internal inconsistencies that derail the model’s reasoning. A clash can happen if the agent accumulates multiple pieces of information that are in conflict.

For example, imagine an agent that fetched data from two sources: One says Flight A departs at 5 PM, and the other says Flight A departs at 6 PM. If both facts end up in the context, the poor model has no way to know which is correct; it may get confused or produce an incorrect or non-similar answer.

Context clash also frequently occurs in multiturn conversations where the model’s earlier attempts at answering are still lingering in the context along with later refined information.

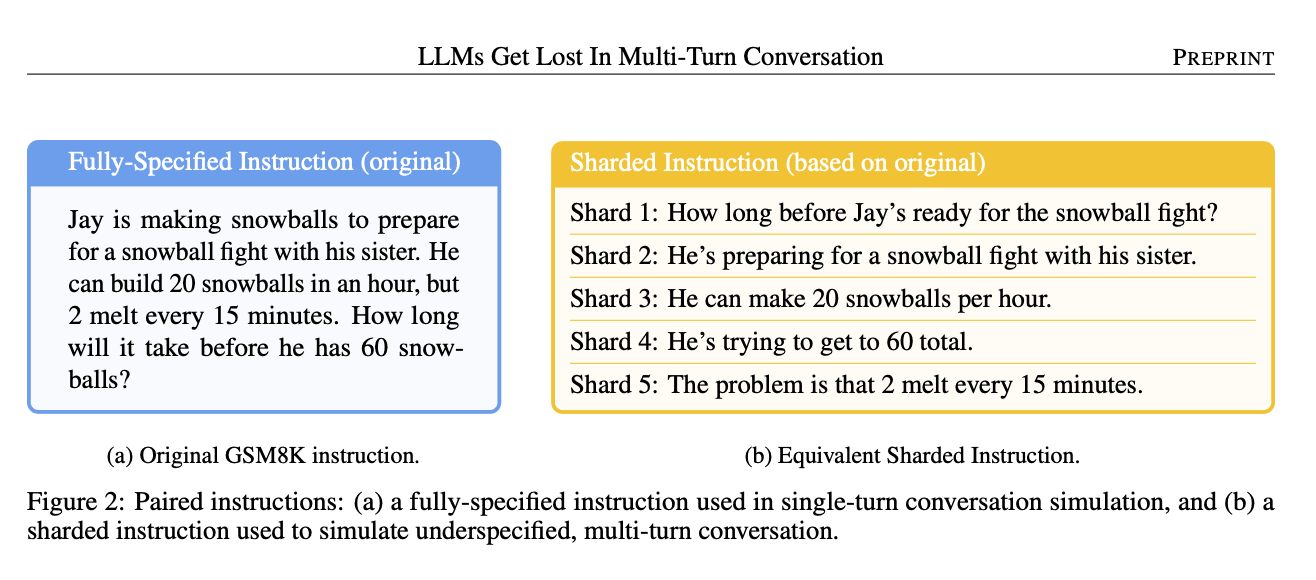

Image source: LLMS gets lost in the mult-turn conversation (Page04)

A research study by Microsoft and Salesforce shows that if you break a complex query into multiple chatbot turns (adding details gradually), the final accuracy drops significantly, compared to giving all details in a single prompt. Why? Because the early turns contain partial or incorrect intermediate answers from the model, and those remain in the context. When the model later tries to answer with all info, its memory still includes those wrong attempts, which conflict with the corrected info and lead it off track. Essentially, the conversation’s context clashes with itself. The model may inadvertently use an outdated piece of context (from an earlier turn) that doesn’t apply after new info is added.

In agent systems, context clash is especially dangerous because an agent might combine outputs from different tools or subagents. If those outputs disagree, the aggregated context is inconsistent. The agent could then get stuck or produce nonsensical results trying to reconcile the contradictions. Preventing context clash involves ensuring the context is fresh and consistent, for instance, clearing or updating any outdated info and not mixing sources that haven’t been vetted for consistency.

Context leakage and knowledge conflicts

In systems where multiple agents or users share a memory store, there’s a risk of information bleeding over between contexts.

For example, if two separate users’ data embeddings reside in the same vector database without proper access control, an agent answering User A’s query might accidentally retrieve some of User B’s memory. This cross-context leak can expose private information or just create confusion in responses.

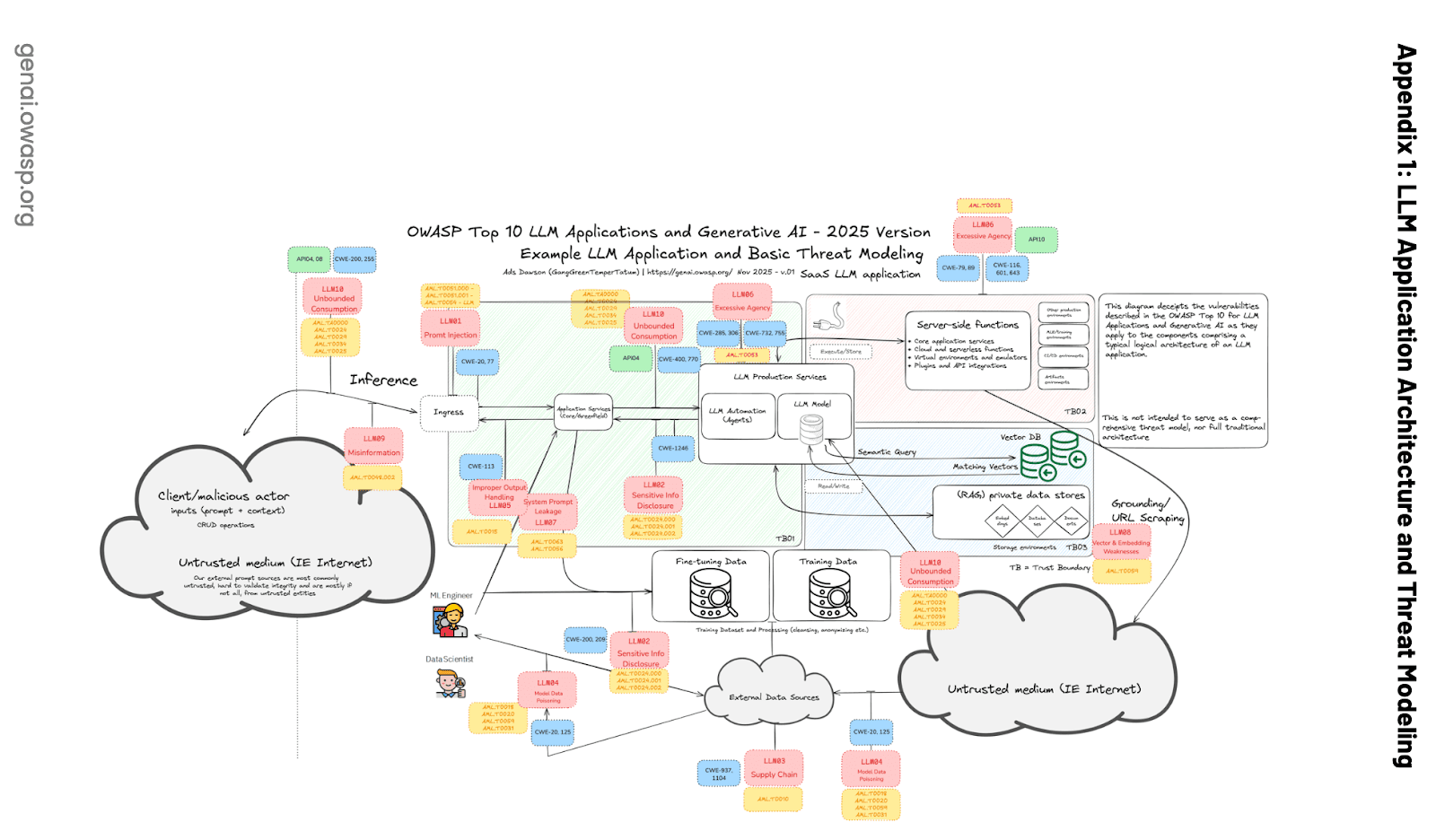

According to the OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications, multitenant vector databases must guard against such leakage:

According to LLM08:2025 Vector and Embedding Weaknesses, one of the common risks is context leakage:

In multi-tenant environments where multiple classes of users or applications share the same vector database, there's a risk of context leakage between users or queries. Data federation knowledge conflict errors can occur when data from multiple sources contradict each other. This can also happen when an LLM can’t supersede old knowledge that it has learned while training, with the new data from Retrieval Augmentation.

Another aspect is that an LLM might have trouble overriding its built-in knowledge with new info from memory. If the model was trained on some fact and the retrieved context says the opposite, the model can get confused about which to trust. Without proper design, the agent could mix up contexts or fail to update old knowledge with new evidence, leading to stale or incorrect answers.

Hallucinations and misinformation

While hallucination (the LLM making up plausible-sounding but false information) is a known problem even without long contexts, poor memory management can amplify it.

If the agent’s memory is lacking a crucial fact, the model may just fill in the gap with a guess, and if that guess then enters the context (poisoning it), the error persists.

The OWASP LLM security report (LLM09:2025 Misinformation) highlights misinformation as a core vulnerability: LLMs can produce confident but fabricated answers, and users may overtrust them. An agent with a bad or outdated long-term memory might confidently cite something that was true last year but is false now, unless its memory is kept up to date.

Overreliance on the AI’s output (by either the user or the agent itself in a loop) can make this worse. If no one ever checks the info in memory, the agent can accumulate falsehoods. This is why RAG is often used to reduce hallucinations: By retrieving an authoritative source, the model doesn’t have to invent facts. But if your retrieval pulls in the wrong document (say, one that contains misinformation) or if an early hallucination isn’t pruned, the system may propagate that misinformation throughout its actions.

The bottom line: Failing to manage memory can lead to incorrect and misleading outputs, which can be damaging, especially if the stakes are high (for example, bad advice in a finance or medical domain). An agent needs mechanisms to verify or correct its memory content, not just unconditionally trust whatever is in the context.

In summary, giving an AI agent an infinitely long memory or dumping every possible thing into its context is not a recipe for success.

Best practices for memory management in LLM applications

To avoid the pitfalls above, developers and researchers devised a number of best practices for managing context and memory in AI systems. These practices aim to keep the AI’s working context lean, relevant, and up to date.Here are some of the key strategies, along with examples of how they help.

RAG: Use targeted context

Much of RAG has already been covered in the earlier section, so this serves as a concise set of practical reminders:

- Use targeted retrieval, not bulk loading: Retrieve only the most relevant chunks instead of pushing entire documents or full conversation histories into the prompt.

- Treat RAG as just-in-time memory recall: Fetch context only when it’s needed, rather than carrying everything forward across turns.

- Prefer relevance-aware retrieval strategies: Approaches like top-k semantic search, Reciprocal Rank Fusion, or tool loadout filtering help reduce noise and improve grounding.

- Larger context windows don’t remove the need for RAG: Two highly relevant paragraphs are almost always more effective than 20 loosely related pages.

That said, RAG isn’t about adding more context; it’s about adding the right context.

Tool loadout

Tool loadout is about giving a model only the tools it actually needs for a task. The term comes from gaming: You pick a loadout that fits the situation. Too many tools slow you down; the wrong ones cause failure. LLMs behave the same way, according to the research paper Less is more. Once you pass ~30 tools, descriptions start overlapping and the model gets confused. Past ~100 tools, failure is almost guaranteed. This isn’t a context window problem, it’s context confusion.

A simple and effective fix is RAG-MCP. Instead of dumping every tool into the prompt, tool descriptions are stored in a vector database and only the most relevant ones are retrieved per request. In practice, this keeps the loadout small and focused, dramatically shortens prompts, and can improve tool selection accuracy by up to 3x.

Smaller models hit this wall even sooner. The research shows an 8B model failing with dozens of tools but succeeding once the loadout is trimmed. Dynamically selecting tools, sometimes with an LLM first, reasoning about what it thinks it needs, can boost performance by 44%, while also reducing power usage and latency. The takeaway is that most agents only need a few tools, but as your system grows, tool loadout and RAG-MCP become first-order design decisions.

Context pruning: Limit the chat history length

If a conversation goes on for many turns, the accumulated chat history can become too large to fit, leading to context overflow or becoming too distracting to the model.

Trimming means programmatically removing or shortening less important parts of the dialogue as it grows. One simple form is to drop the oldest turns of the conversation when you hit a certain limit, keeping only the latest N messages. More sophisticated pruning might remove irrelevant digressions or previous instructions that are no longer needed. The goal is to keep the context window uncluttered by old news.

For example, if the agent solved a subproblem 10 turns ago and we have since moved on, we might delete that portion of the history from the context (assuming it won’t be needed further). Many chat-based implementations do this: They maintain a rolling window of recent messages.

Trimming can be as simple as “forgetting” the earliest parts of a conversation once they’ve been summarized or are deemed irrelevant. By doing so, we reduce the risk of context overflow errors and also reduce context distraction, so the model won’t see and get sidetracked by old or off-topic content. This approach is very similar to how humans might not remember every word from an hour-long talk but will retain the highlights.

If you’re confused about context pruning, as highlighted by the author Drew Breunig here, usage of the Provence (`naver/provence-reranker-debertav3-v1`) model, a lightweight (1.75 GB), efficient, and accurate context pruner for question answering, can make a difference. It can trim large documents down to only the most relevant text for a given query. You can call it in specific intervals.

Here’s how we invoke the `provence-reranker` model in our code to prune the context:

We use the Provence reranker model (`naver/provence-reranker-debertav3-v1`) to score sentence relevance. Threshold-based filtering keeps sentences above the relevance threshold. Also, we introduce a fallback mechanism, where we return to the original context if pruning fails. Finally, statistics logging tracks reduction percentage in verbose mode.

Context summarization: Condense older information instead of dropping it entirely

Summarization is a companion to trimming. When the history or knowledge base becomes too large, you can employ the LLM to generate a brief summary of the important points and use that summary in place of the full content going forward, as we performed in our code above.

For example, if an AI assistant has had a 50-turn conversation, instead of sending all 50 turns to the model on turn 51 (which likely won’t fit), the system might take turns 1–40, have the model summarize them in a paragraph, and then only supply that summary plus the last 10 turns in the next prompt. This way, the model still knows what was discussed without needing every detail. Early chatbot users did this manually by asking, “Can you summarize what we’ve talked about so far?” and then continuing in a new session with the summary. Now it can be automated. Summarization not only saves context window space but can also reduce context confusion/distraction by stripping away extra detail and retaining just the salient facts.

Here’s how we use OpenAI models (you can use any LLMs) to condense context while preserving all relevant information, eliminating redundancy and duplication.

Importantly, when the context is summarized, the model is less likely to get overwhelmed by trivial details or past errors (assuming the summary is accurate).

However, summarization has to be done carefully. A bad summary might omit a crucial detail or even introduce an error. It’s essentially another prompt to the model (“summarize this”), so it can hallucinate or lose nuance. Best practice is to summarize incrementally and perhaps keep some canonical facts unsummarized.

Nonetheless, it has proven very useful. In the Gemini agent scenario, summarizing the context every ~100k tokens was a way to counteract the model’s tendency to repeat itself. The summary acts like a compressed memory of the conversation or data. As developers, we can implement this by having an agent periodically call a summarization function (maybe a smaller LLM or a dedicated routine) on the conversation history or a long document. The resulting summary replaces the original content in the prompt. This tactic is widely used to keep contexts within limits and distill the information.

Context quarantine: Isolate contexts when possible

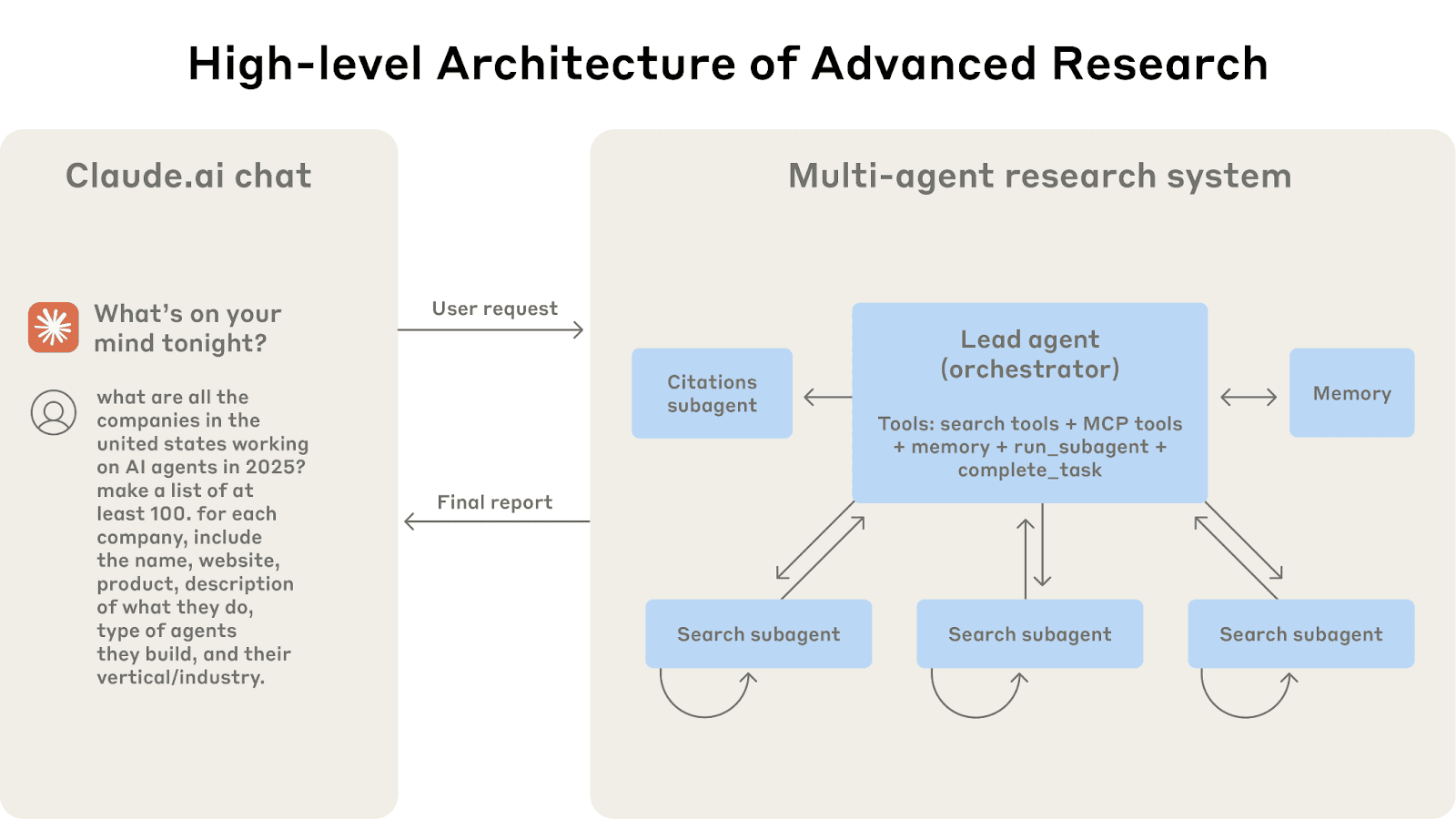

This is more relevant in complex agent systems or multistep workflows. The idea of context segmentation is to split a big task into smaller, isolated tasks, each with its own context, so that you never accumulate one enormous context that contains everything. Each subagent or subtask works on a piece of the problem with a focused context, and then a higher-level agent, or supervisor or coordinator integrates the results.

The multi-agent architecture in action: User queries flow through a lead agent that creates specialized subagents to search for different aspects in parallel.

Image source: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/multi-agent-research-system

Anthropic’s research strategy uses multiple subagents, each investigating a different aspect of a question, with their own context windows, and a lead agent that reads the distilled results from those subagents. This parallel, modular approach means that no single context window gets too bloated. It also reduces the chance of irrelevant information mixing, each thread stays on topic (no context confusion), and it doesn’t carry unnecessary baggage when answering its specific subquestion. In a sense, it’s like running separate threads of thought that only share their outcomes, not their entire thought process.

In multi-agent systems, this approach is essential. If Agent A is handling task A and Agent B is handling task B, there’s no reason for either agent to consume the other’s full context unless it’s truly required. Instead, agents can exchange only the necessary information. For example, Agent A can pass a consolidated summary of its findings to Agent B via a supervisor agent, while each subagent maintains its own dedicated context thread. This setup doesn’t require human-in-the-loop intervention; it relies on a supervisory agent with enabled tools with minimal and controlled context sharing.

Nonetheless, designing your system so that agents or tools operate with minimal necessary context overlap can greatly enhance clarity and performance. Think of it as microservices for AI, each component deals with its context, and you pass messages between them in a controlled way, instead of one monolithic context.These best practices are often used in combination. Also, this gives you the flexibility to trim trivial history, summarize important older messages or conversations, offload the detailed logs to Elasticsearch for long-term context, and use retrieval to bring back anything relevant when needed.

As mentioned here, the guiding principle is that context is a limited and precious resource. You want every token in the prompt to earn its keep, meaning it should contribute to the quality of the output. If something in memory is not pulling its weight (or worse, actively causing confusion), then it should be pruned, summarized, or kept out.

As developers, we can now program the context just like we program code, deciding what information to include, how to format it, and when to omit or update it. By following these practices, we can give LLM agents the much-needed context to perform tasks without falling victim to the failure modes described earlier. The result is agents that remember what they should, forget what they don’t need, and retrieve what they require just in time.

Conclusion

Memory isn’t something you add to an agent; it’s something you engineer. Short-term memory is the agent’s working scratch pad, and long-term memory is its durable knowledge store. RAG is the bridge between the two, turning a passive datastore, like Elasticsearch, into an active recall mechanism that can ground outputs and keep the agent current.

But memory is a double-edged sword. The moment you let context grow unchecked, you invite poisoning, distraction, confusion, and clashes, and in shared systems, even data leakage. That’s why the most important memory work isn’t “store more,” it’s “curate better”: Retrieve selectively, prune aggressively, summarize carefully, and avoid mixing unrelated contexts unless the task truly demands it.

In practice, good context engineering looks like good systems design: smaller, sufficient contexts, controlled interfaces between components, and a clear separation between raw and the distilled state you actually want the model to see. Done right, you don’t end up with an agent that remembers everything - you end up with an agent that remembers the right things, at the right time, for the right reason.