Get hands-on with Elasticsearch: Dive into our sample notebooks in the Elasticsearch Labs repo, start a free cloud trial, or try Elastic on your local machine now.

We recently replaced key parts of Elasticsearch’s hash table implementation with a Swiss-style design and observed up to 2–3x faster build and iteration times on uniform, high-cardinality workloads. The result is lower latency, better throughput, and more predictable performance for Elasticsearch Query Language (ES|QL) stats and analytics operations.

Why this matters

Most typical analytical workflows eventually boil down to grouping data. Whether it’s computing average bytes per host, counting events per user, or aggregating metrics across dimensions, the core operation is the same — map keys to groups and update running aggregates.

At a small scale, almost any reasonable hash table works fine. At the large scale (hundreds of millions of documents and millions of distinct groups) details start to matter. Load factors, probing strategy, memory layout, and cache behavior can make the difference between linear performance and a wall of cache misses.

Elasticsearch has supported these workloads for years, but we’re always looking for opportunities to modernize core algorithms. As such, we evaluated a newer approach inspired by Swiss tables and applied it to how ES|QL computes statistics.

What are Swiss tables, really?

Swiss tables are a family of modern hash tables popularized by Google’s SwissTable and later adopted in Abseil and other libraries.

Traditional hash tables spend a lot of time chasing pointers or loading keys just to discover that they don’t match. Swiss tables’ defining feature is the ability to reject most probes using a tiny cache-resident array structure, stored separately from the keys and values, called control bytes, to dramatically reduce memory traffic.

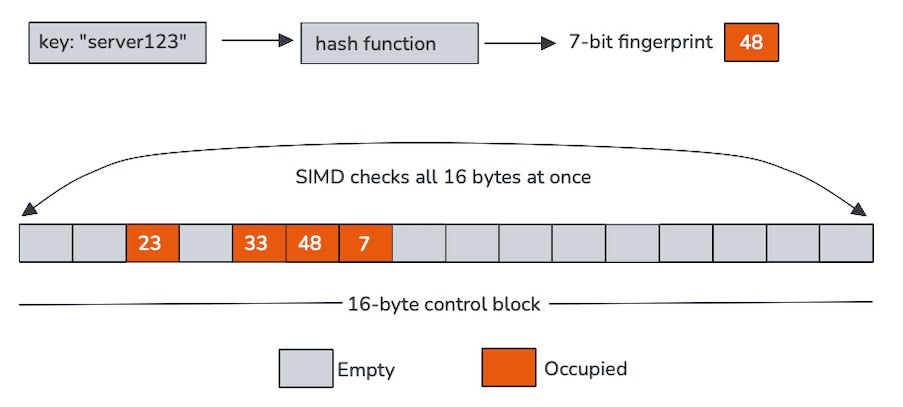

Each control byte represents a single slot and, in our case, encodes two things: whether the slot is empty, and a short fingerprint derived from the hash. These control bytes are laid out contiguously in memory, typically in groups of 16, making them ideal for single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) processing.

Instead of probing one slot at a time, Swiss tables scan an entire control-byte block using vector instructions. In a single operation, the CPU compares the fingerprint of the incoming key against 16 slots and filters out empty entries. Only the few candidates that survive this fast path require loading and comparing the actual keys.

This design trades a small amount of extra metadata for much better cache locality and far fewer random loads. As the table grows and probe chains lengthen, those properties become increasingly valuable.

SIMD at the center

The real star of the show is SIMD.

Control bytes are not just compact, they’re also explicitly designed to be processed with vector instructions. A single SIMD compare can check 16 fingerprints at once, turning what would normally be a loop into a handful of wide operations. For example:

In practice, this means:

- Fewer branches.

- Shorter probe chains.

- Fewer loads from key and value memory.

- Much better utilization of the CPU’s execution units.

Most lookups never make it past the control-byte scan. When they do, the remaining work is focused and predictable. This is exactly the kind of workload that modern CPUs are good at.

SIMD under the hood

For readers who like to peek under the hood, here’s what happens when inserting a new key into the table. We use the Panama Vector API with 128-bit vectors, thus operating on 16 control bytes in parallel.

The following snippet shows the code generated on an Intel Rocket Lake with AVX-512. While the instructions reflect that environment, the design does not depend on AVX-512. The same high-level vector operations are emitted on other platforms using equivalent instructions (for example, AVX2, SSE, or NEON).

Each instruction has a clear role in the insertion process:

vmovdqu: Loads 16 consecutive control bytes into the 128-bitxmm0register.vpbroadcastb: Replicates the 7-bit fingerprint of the new key across all lanes of thexmm1register.vpcmpeqb: Compares each control byte against the broadcasted fingerprint, producing a mask of potential matches.kmovq+test: Moves the mask to a general-purposes register and quickly checks whether a match exists.

Finally, we settled on probing groups of 16 control bytes at a time, as benchmarking showed that expanding to 32 or 64 bytes with wider registers provided no measurable performance benefit.

Integration in ES|QL

Adopting Swiss-style hashing in Elasticsearch was not just a drop-in replacement. ES|QL has strong requirements around memory accounting, safety, and integration with the rest of the compute engine.

We integrated the new hash table tightly with Elasticsearch’s memory management, including the page recycler and circuit breaker accounting, ensuring that allocations remain visible and bounded. Elasticsearch's aggregations are stored densely and indexed by a group ID, keeping the memory layout compact and fast for iteration, as well as enabling certain performance optimizations by allowing random access.

For variable-length byte keys, we cache the full hash alongside the group ID. This avoids recomputing expensive hash codes during probing and improves cache locality by keeping related metadata close together. During rehashing, we can rely on the cached hash and control bytes without inspecting the values themselves, keeping resizing costs low.

One important simplification in our implementation is that entries are never deleted. This removes the need for tombstones (markers to identify previously occupied slots) and allows empty slots to remain truly empty, which further improves probe behavior and keeps control-byte scans efficient.

The result is a design that fits naturally into Elasticsearch’s execution model while preserving the performance characteristics that make Swiss tables attractive.

How does it perform?

At small cardinalities, Swiss tables perform roughly on par with the existing implementation. This is expected: When tables are small, cache effects dominate less and there is little probing to optimize.

As cardinality increases, the picture changes quickly.

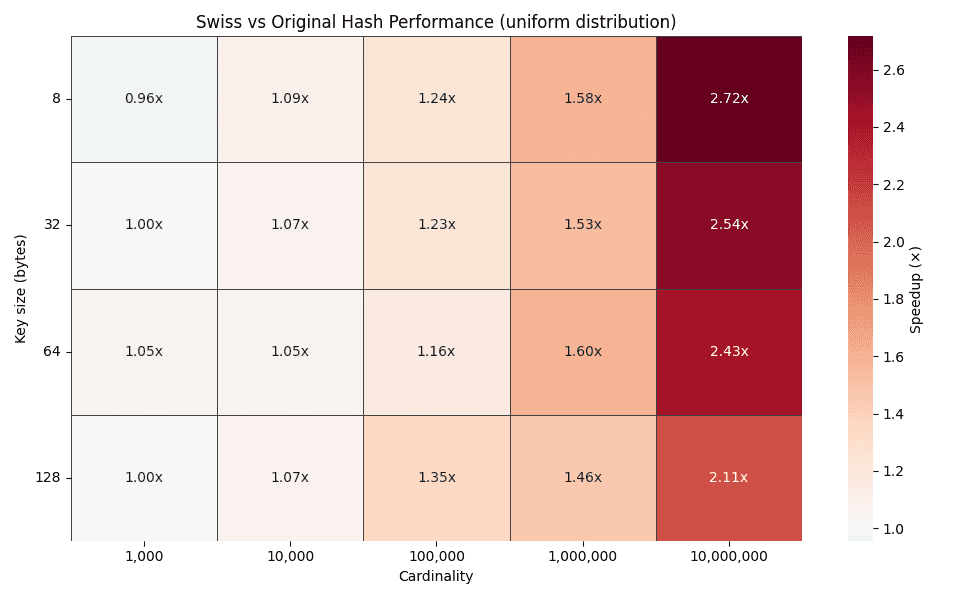

The heatmap above plots time improvement factors for different key sizes (8, 32, 64, and 128 bytes) across cardinalities from 1,000 up to 10,000,000 groups. As cardinality grows, the improvement factor steadily increases, reaching up to 2–3x for uniform distributions.

This trend is exactly what the design predicts. Higher cardinality leads to longer probe chains in traditional hash tables, while Swiss-style probing continues to resolve most lookups inside SIMD-friendly control-byte blocks.

Cache behavior tells the story

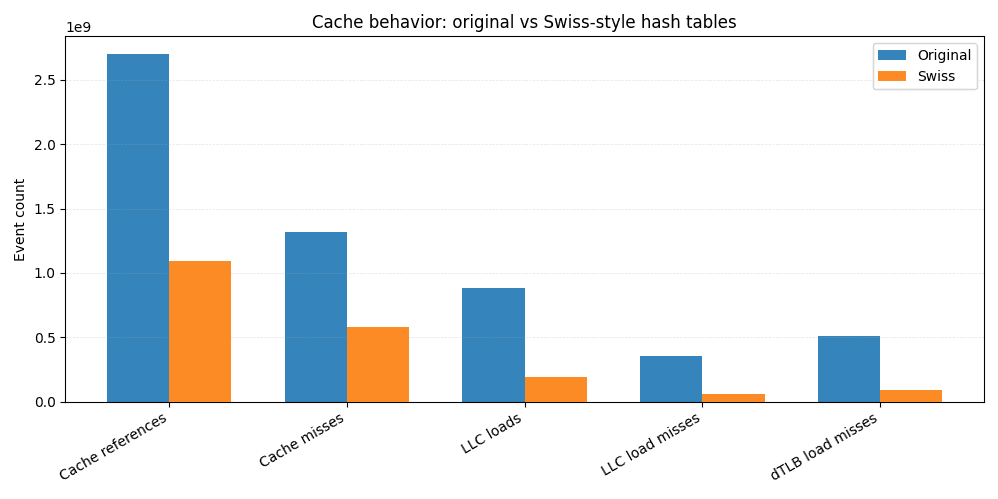

To better understand the speedups, we ran the same JMH benchmarks under Linux perf and captured cache and TLB statistics.

Compared to the original implementation, the Swiss version performs about 60% fewer cache references overall. Last-level cache loads drop by more than 4x, and LLC load misses fall by over 6x. Since LLC misses often translate directly into main-memory accesses, this reduction alone explains a large portion of the end-to-end improvement.

Closer to the CPU, we see fewer L1 data cache misses and nearly 6x fewer data TLB misses, pointing to tighter spatial locality and more predictable memory access patterns.

This is the practical payoff of SIMD-friendly control bytes. Instead of repeatedly loading keys and values from scattered memory locations, most probes are resolved by scanning a compact, cache-resident structure. Less memory touched means fewer misses, and fewer misses mean faster queries.

Wrapping up

By adopting a Swiss-style hash table design and leaning hard into SIMD-friendly probing, we achieved 2–3x speedups for high-cardinality ES|QL stats workloads, along with more stable and predictable performance.

This work highlights how modern CPU-aware data structures can unlock substantial gains, even for well-trodded problems, like hash tables. There is more room to explore here, like additional primitive type specializations and use in other high-cardinality paths, like joins, all of which are just part of the broader and ongoing effort to continually modernize Elasticsearch internals.

If you’re interested in the details or want to follow the work, check out this pull request and meta issue tracking progress on Github.

Happy hashing!