Get hands-on with Elasticsearch: Dive into our sample notebooks in the Elasticsearch Labs repo, start a free cloud trial, or try Elastic on your local machine now.

Over the last decade, NeurIPS has become one of the premier academic conferences for AI and machine learning, where the most important papers are presented and where researchers in this community meet and network.

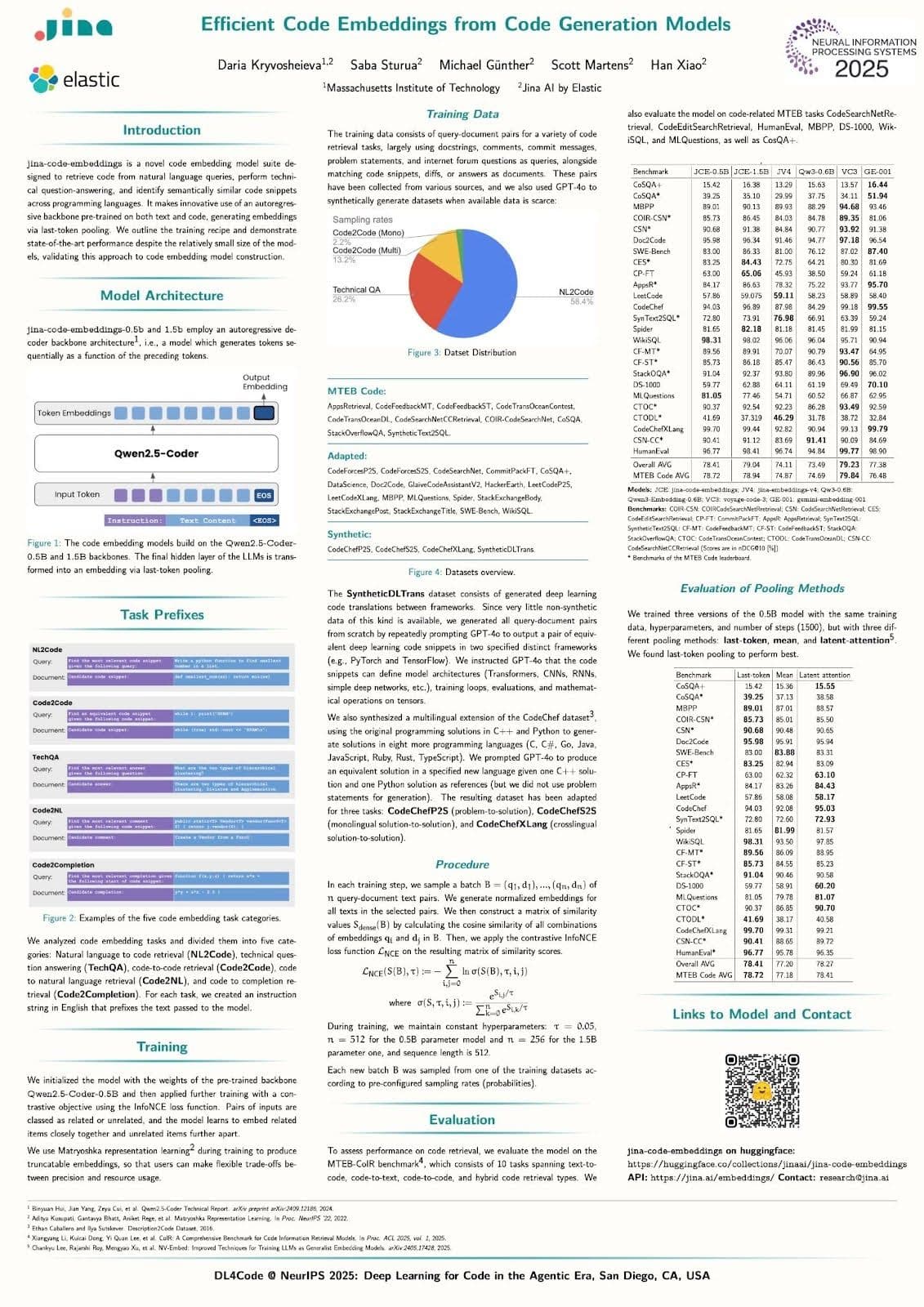

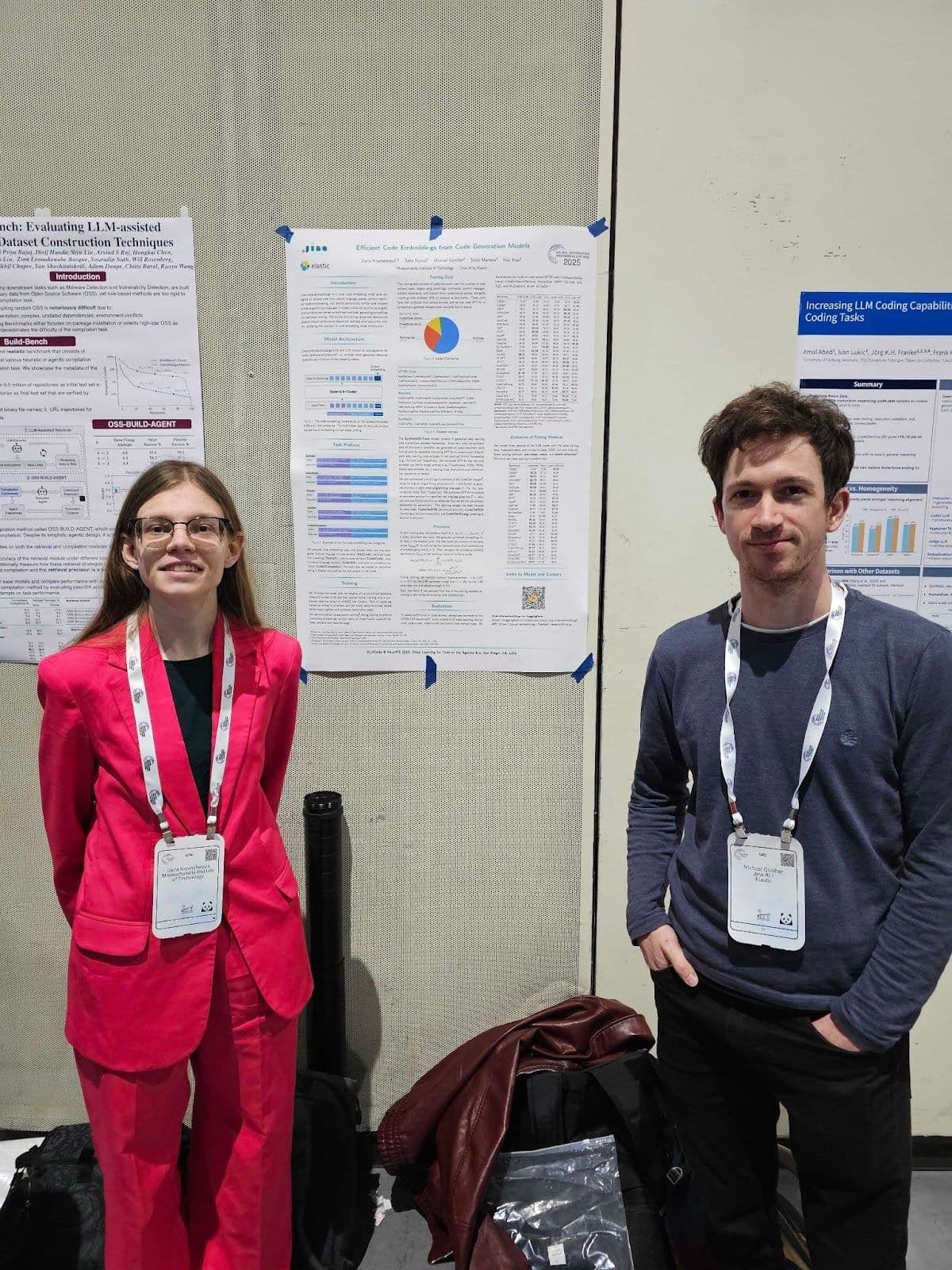

Jina by Elastic engineers Michael Günther and Florian Hönicke attended this year’s conference in San Diego with Daria Kryvosheieva. They presented her internship project, the jina-code-embeddings models, at the Deep Learning for Code (DL4C) workshop.

Jina’s poster presentation at the DL4C workshop. Read the paper on arXiv: Efficient Code Embeddings from Code Generation Models.

Coding agents and automated coding are very popular research areas and were prominent topics at this year’s NeurIPS, with more than 60 papers and hundreds of participants at the DL4C workshop. AI models that can generate code are not just important to software developers. They also they enable AI agents to execute code to solve problems and interact with databases and other applications, such as by writing their own SQL queries,creating SVG and HTML on the fly for display, and more.

There’s a lot of interest in AI applications for the IT industry, including Streams, which is using AI to interpret system logs.

Jina’s contribution to the field is a very compact, high-performance embedding model dedicated to retrieving code and computer documentation from knowledge bases and repositories, with applications to integrated development environments (IDEs) code assistants, and IT-centric retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) applications.

Daria Kryvosheieva (left) and Michael Günther (right) with their poster at NeurIPS.

Overall, the conference found a good balance between theoretical work and applied research.

San Diego in early December was mild and pleasant, and the city has an easygoing atmosphere. People lingered outside between sessions and, in the evening, the cafés and bars were full of people with conference badges.

Impressions of San Diego from NeurIPS 2025 at the San Diego Convention Center

We learned a lot at NeurIPS 2025 and enjoyed the trip to a city much warmer than Berlin at this time of year. In this post, we briefly share what we found most valuable at the conference.

Model merging: Theory, practice, and applications

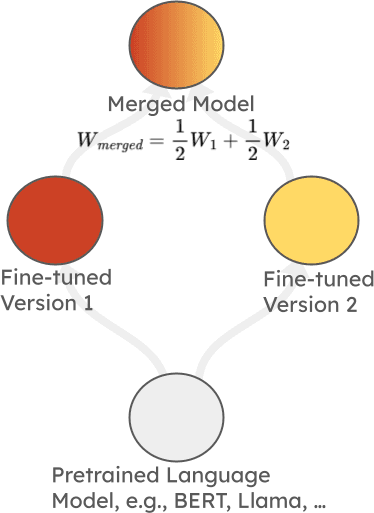

This tutorial, from Marco Ciccone, Malikeh Ehghaghi, and Colin Raffel, was particularly interesting. Over the last few years, model merging has become a widely used technique for making AI models more robust when fine-tuned for specialized applications. In the simplest case, it involves combining two or more fine-tuned models, derived from the same base model, by averaging their weights, as in the image below:

Simple weight averaging of two fine-tuned models derived from the same base model.

As simplistic as this sounds, it usually works and leads to models that perform better (or at least not much worse) on both fine-tuned tasks,, as well as retaining the performance of the base model on nonspecialized tasks.

The tutorial provided an overview of recent advances in this very active research area, especially developments in more sophisticated merging methods beyond simple weight averaging. Notably:

- TIES-Merging, which tries to mitigate merging conflicts between weights by, among other things, selecting subsets of the weights.

- Fisher Merging and RegMean, which involve using activation information to improve outcomes from model mergers.

There was also a summary of model development techniques deployed at the largest AI labs, like Google DeepMind and Cohere, which both appear to rely on model merging, ensuring continuing interest and development in this area.

Interesting research

We also attended oral presentations and poster sessions, and several struck us as particularly valuable.

Large language diffusion models

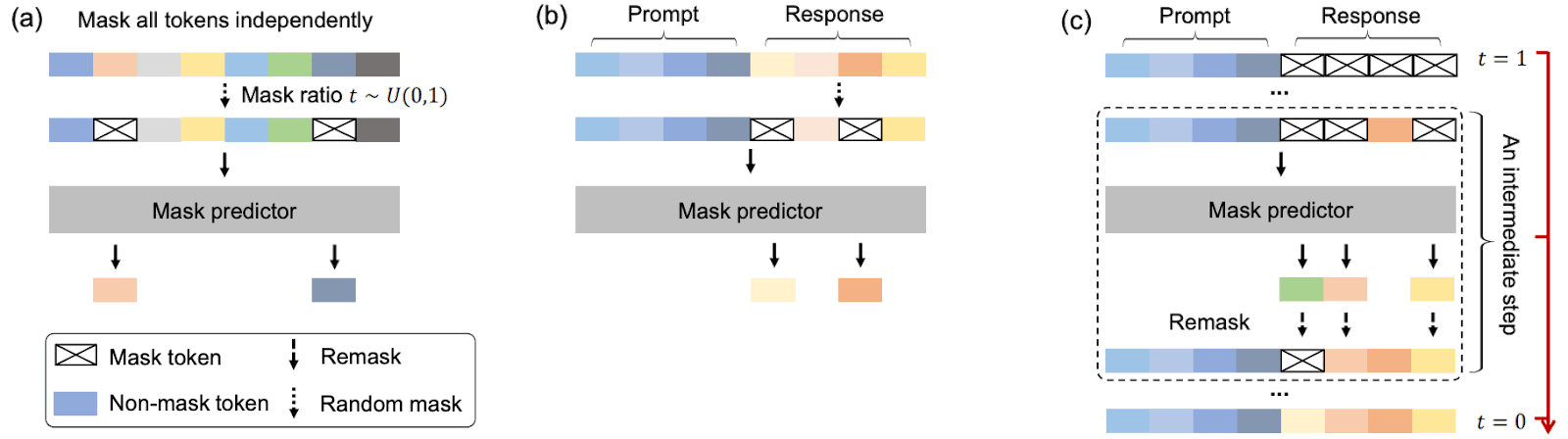

Diffusion models work very differently from most language models. Language models are generally trained using autoregressive methods: Given some length of text, they receive training to produce the next token. Diffusion language models, in contrast, are trained with texts with some tokens masked out, and they learn to fill them in. They generate text nonlinearly, passing over it multiple times and adding tokens in no particular order, instead of generating one word after the other. Diffusion was originally applied very successfully to image generation but has only recently been widely applied to text.

This research applies the diffusion approach to a relatively large transformer-based language model (8 billion parameters) as pretraining and supervised fine-tuning. During pretraining, the model learns to fill in text with random (up to 100%) masked text. During supervised fine-tuning, the prompt is never masked, so it can learn to generate text from instructions.

Overview of large language diffusion with masking (LLaDA), from Figure 2 of the paper. Original caption: (a) Pre-training. LLaDA is trained on text with random masks applied independently to all tokens at the same ratio t ∼ U[0, 1]. (b) SFT. Only response tokens are possibly masked. (c) Sampling. LLaDA simulates a diffusion process from t = 1 (fully masked) to t = 0 (unmasked), predicting all masks simultaneously at each step with flexible remask strategies.

The resulting model shows comparable performance to autoregressively trained models across many tasks, while excelling in some domains, particularly math-related tasks. This is a very promising direction for language modeling research, and we’re curious to see whether diffusion models will become more prominent for training language models and whether they’re applied to embedding models, as well.

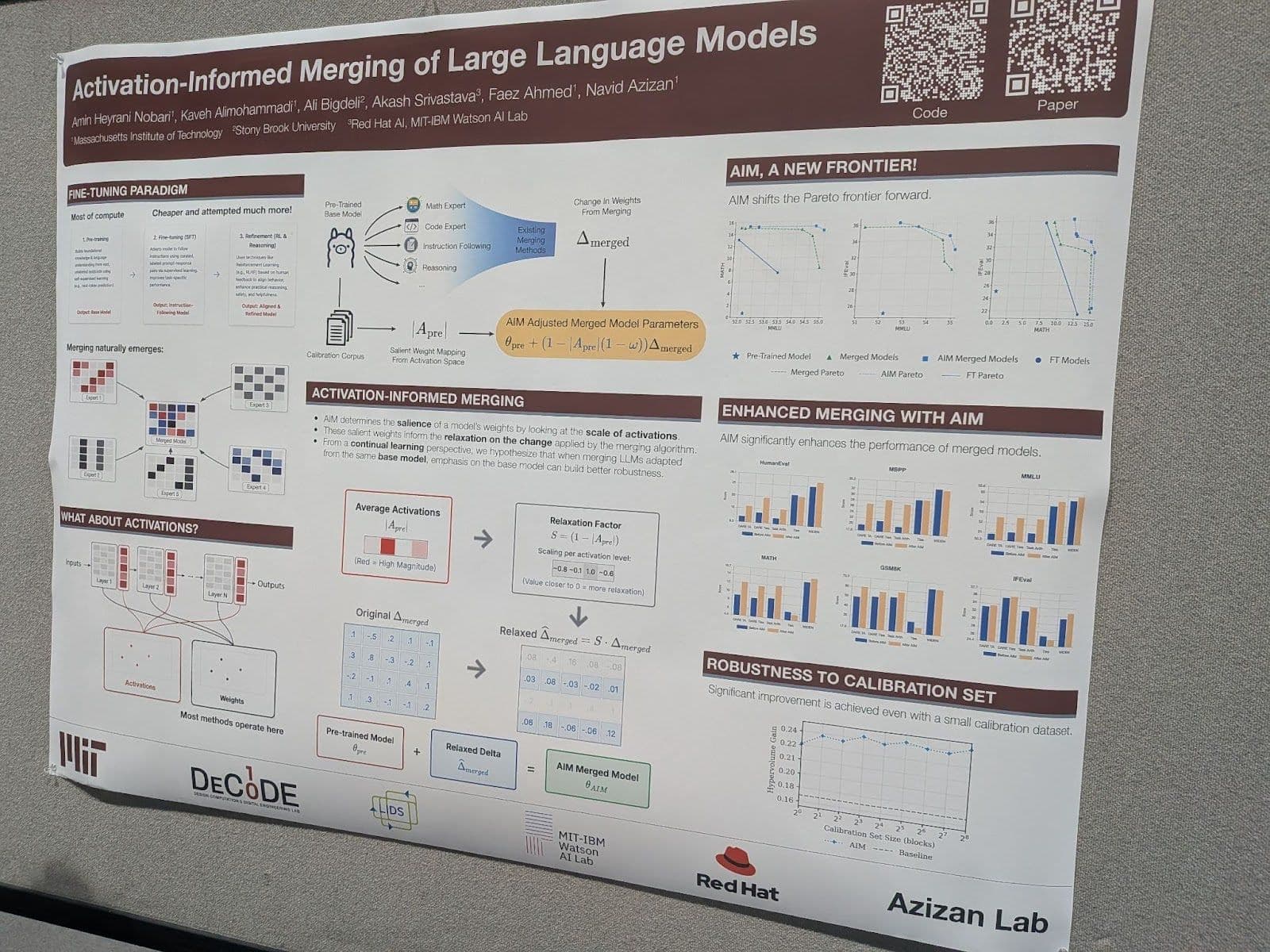

Activation-informed merging of large language models

This paper proposes another technique for improving model merging. The intuition behind this work is identifying and preserving the most important weights of the base model when merging one or more fine-tuned models.

Poster presentation at NeurIPS 2025: “Activation-Informed Merging of Large Language Models.”

It uses a calibration dataset to obtain the average activations of all layers in the model and identifies the most critical weights by calculating the influence of each weight on model activation levels. It then uses this to determine which weights should not be dramatically changed during merging.

This approach is compatible with using other model-merging techniques. The authors show significant improvements when using this method in combination with various other merging methods.

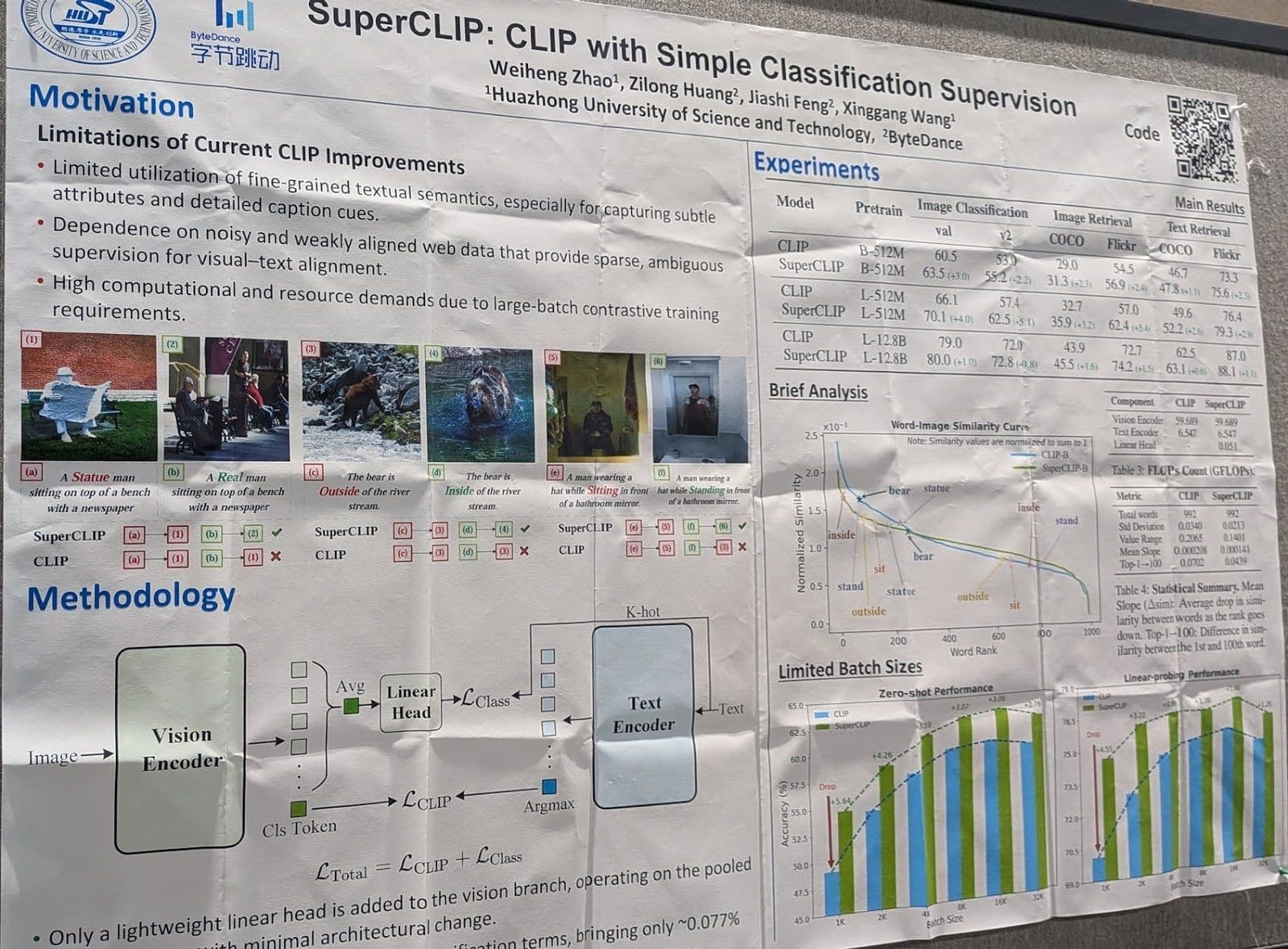

SuperCLIP: CLIP with simple classification supervision

A well-known problem with image-text models trained using Contrastive Language Image Pretraining (CLIP) is that they aren’t good at capturing fine-grained textual information, due to architectural limitations and to the nature of the web-scraped data typically used to train vision models. During the development of the Jina-CLIP models, we also identified that CLIP models are generally bad at understanding more complex texts because they’re trained on short texts. We compensated by adding longer texts to our training data.

This paper proposes an alternative solution: adding a novel classification loss component to the ordinary CLIP loss.

Poster presentation at NeurIPS 2025: "SuperCLIP: CLIP with Simple Classification Supervision."

It relies on added layers during training that use output image tile embeddings to predict the text tokens in its description. Training optimizes for both this objective and the CLIP loss at the same time.

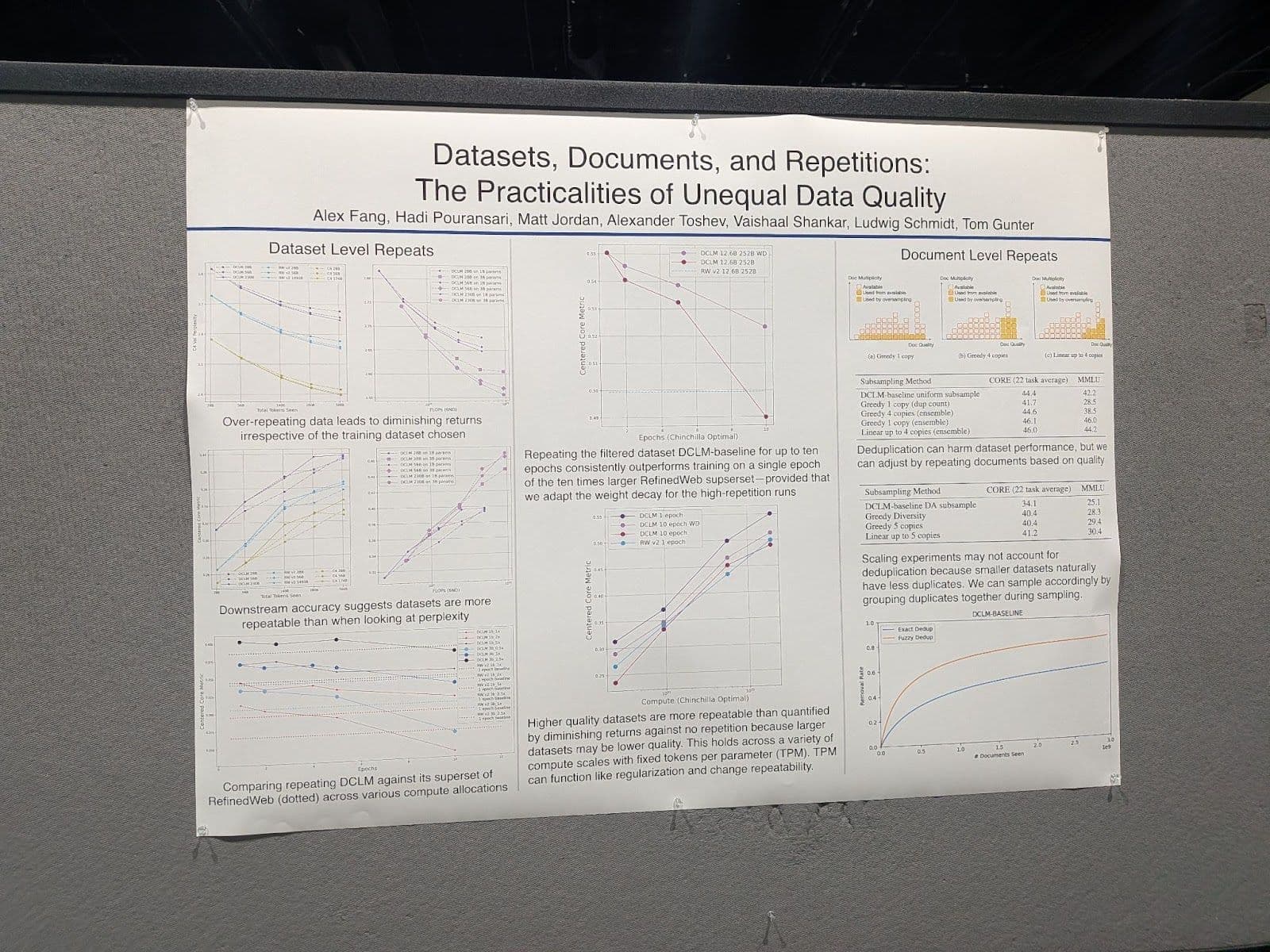

Datasets, documents, and repetitions: The practicalities of unequal data quality

This paper addresses issues in training data quality for large language models (LLMs). Typically, such models are trained with large datasets that routinely contain duplicated items. However, paradoxically, deduplication often produces worse results.

The authors propose an explanation for this confusing finding and offer some elements of a solution.

Poster presentation at NeurIPS 2025: “Datasets, Documents, and Repetitions: The Practicalities of Unequal Data Quality.

Their principal findings are:

- Large models suffer more when training data is duplicated than small models do.

- Duplicating high-quality documents improves training outcomes or at least does less to reduce them than low-quality ones do.

- High-quality documents are more likely to appear multiple times in real-world training datasets.

These last two points in particular explain the paradox of deduplication.

Does reinforcement learning really incentivize reasoning capacity in LLMs beyond the base model?

Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR)is a method of fine-tuning LLMs for reasoning using reinforcement learning in a way that doesn’t require human labeling because the solutions to training problems are automatically verifiable. This contrasts with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), where direct human supervision is required during training. For example, this can mean training models to solve math problems or perform coding tasks where the output can be independently tested by machines, that is, checking the solution to a math problem automatically or running unit tests to show that a block of code works correctly.

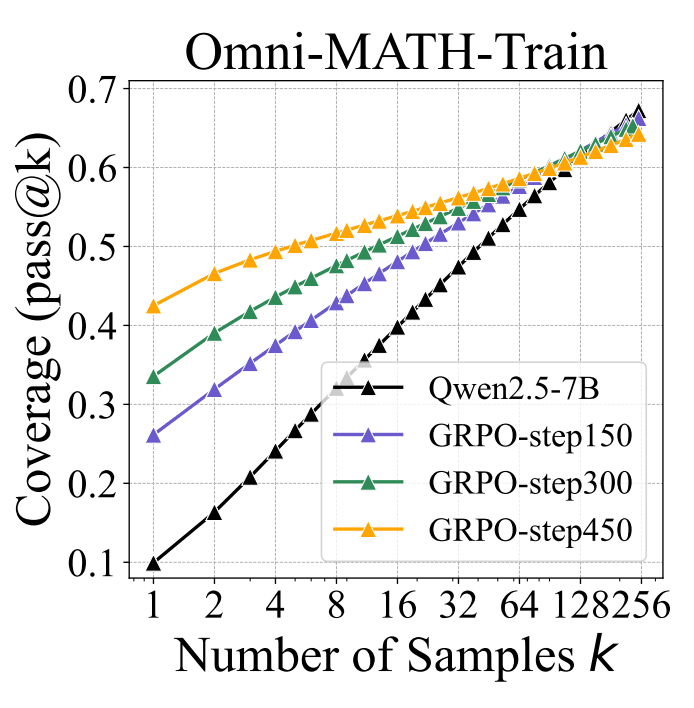

Accuracy as a function of the number of times the model iterated over its answer (labeled “k”), at different stages of training, for the baseline Qwen2.5-7B model and for the model trained using RLVR with the Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) algorithm. From Figure 1 from the paper. This shows that RLVR training significantly improves the accuracy of the first try, but the benefits fall dramatically for multiple passes.

The authors’ test methodology is to assess the number of correct answers for a set of problems, given a varying number of attempts to answer. Each attempt is done by sampling an answer during the generation process. They compare the model after different numbers of RLVR training epochs the model has had. They show that their training substantially improves the accuracy of the model’s answer, if only given one or a few chances, but not if given many. This suggests that they’ve increased the probability of the right answer, but they haven’t really improved the reasoning capabilities of the model.

Conclusion

Measured by conference activity, research in AI looks like it’s still undergoing explosive growth, with no end in sight. Academic work remains very relevant and is especially important for AI developers who don’t have billions of dollars to rent data centers for research.

However, this explosive growth also makes it more and more difficult to follow everything that’s going on.

Here at Elastic, and especially on the Jina team, we’re always excited about what comes next for AI, and we do our best to stay on top of new developments and emergent directions for research. We hope this article gives you a taste of that excitement and a glimpse into the kind of work going on in search AI today.