Elasticsearch is packed with new features to help you build the best search solutions for your use case. Learn how to put them into action in our hands-on webinar on building a modern Search AI experience. You can also start a free cloud trial or try Elastic on your local machine now.

One of the biggest challenges in integrating large language models (LLMs) into search pipelines is the complexity of navigating the space of possibilities that they provide. This blog focuses on a small set of concrete query rewriting (QR) strategies, using LLM-generated keywords, pseudo-answers, or enriched terms. We specifically focus on how to best use the LLM's output to strategically boost the original query's results to maximize search relevance and recall.

LLMs and search engines: An exploration of query rewriting strategies for search improvement

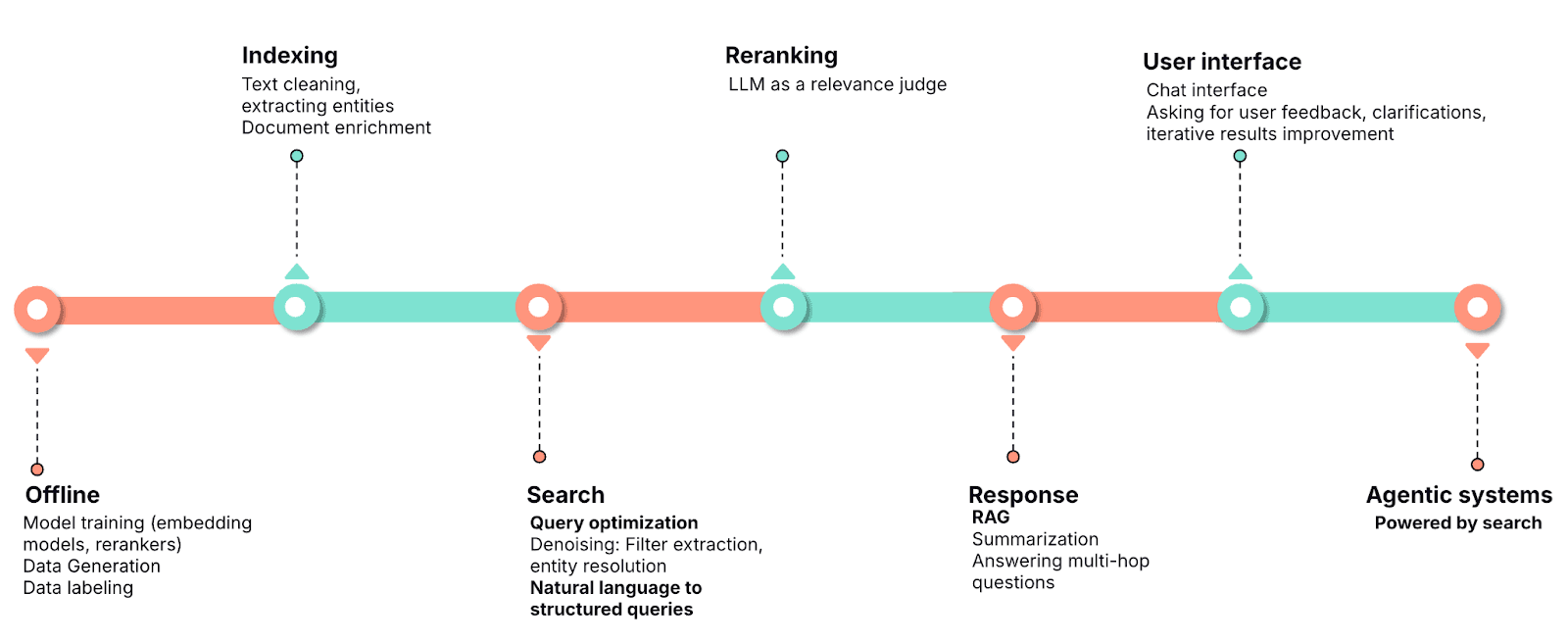

The integration of large language models (LLMs) with search engines represents a significant advancement in the fields of search and AI. This integration can take many forms, depending on the application [1]. On one hand, search engines can enhance LLMs by grounding their generation in freshly retrieved data, a strategy that’s commonly referred to as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). On the other hand, LLMs can improve search engines by optimizing various stages of the search pipeline.

The search pipeline typically consists of three main components: indexing, first-stage retrieval, and reranking. LLMs can contribute at each of these stages. During indexing, LLMs can assist with data preparation tasks, such as text cleaning, entity extraction, and document enrichment by adding domain knowledge, synonyms, or clarifications. In the first-stage retrieval, LLMs can optimize user queries by rewriting them in natural language to improve retrieval accuracy or by mapping them to structured queries (for example, domain‑specific language–style [DSL-style] or Elasticsearch Query Language–style [ES|QL-style] queries) [2]. This blog focuses on query optimization strategies for this stage.

While there is some research on using LLMs as rerankers [3], the literature is less extensive. Technical blogs on the topic suggest that LLMs as rerankers may not always be the optimal choice, though this area remains an active field of exploration [4,5].

The advancements in LLMs have also unlocked new possibilities beyond the traditional indexing and retrieval stages. For example, LLMs can be used to generate natural language responses grounded in retrieved data (RAG). Users increasingly anticipate coherent, natural language responses to their queries, which are also dependable and guaranteed to be based on retrieval data. This is a significant shift in user expectation, occurring quickly since LLM-integrated search engines became generally available, demonstrating a major improvement in user experience. A language model that can understand intent, retrieve data, and synthesize information is especially valuable in multi-hop scenarios where a query requires combining information from various sources.

This is even clearer when looking at the application of LLMs in the creation of interactive, conversational search interfaces. These interfaces allow users to submit queries, provide feedback on responses, or introduce clarifications, enabling iterative improvements to the results, while making use of the historical context of the conversation. Taking this a step further, integrating LLMs with autonomous capabilities, such as planning, retrieving, reasoning, and decision-making, can lead to the development of agentic search systems. These systems can refine results based on user feedback or self-evaluation, creating a dynamic and intelligent search experience.

Finally, LLMs are widely used in search tool development, from data generation to serving as backbones for embedding and reranking models [6,7,8]. Synthetic data generation has become a common step in training retrieval models, and LLMs are increasingly being used as judges to generate labels for training and evaluation.

Image 1. LLM applications in the retrieval pipeline.

Query rewriting and optimization strategies

Query rewriting strategies are best understood by categorizing user queries into two main types: retrieval and computational.

Retrieval queries

Unlike computational queries, the user's intent here is information retrieval, not calculation. These are the standard queries handled by retrieval algorithms, like lexical and vector search. For example, for the following query:

"What is the origin of COVID-19?"

texts providing answers or context relevant to the query are targeted.

Computational queries

These queries require calculation, aggregation, or structured filtering to produce an answer. They must be translated from natural language into a structured query language, like Elasticsearch DSL or ES|QL.

For example, a query like:

"What was the average amount spent by customers who placed more than five orders in the last month?"

Assuming that the information on the orders and customers can be found in some available index, this query requires more than simple text matching. It involves filtering by a date range, grouping by customer, calculating order counts, filtering customers with fewer than five orders, and computing the final average. In this case, the LLM's task is to parse the natural language and generate the corresponding structured query to execute these calculations.

Another example would be:

"Which universities in Germany have an acceptance rate below 20%, and what is their average tuition fee?"

When there is no indexed document that contains that specific information, but rather there might be documents containing acceptance rate information separately from tuition fees information.

In computational queries, the model is essentially expected to decompose the query into a retrievable informational query and a calculation that can be performed when the retrieved data is available, or to build a structured query that can do both.

| Query type | Primary mechanisms | Example | Query rewriting task |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrieval | Lexical and vector search. | "What is the origin of COVID-19?" | Optimize the query's text to improve lexical or vector matching. |

| Computational | Calculation, aggregation, or structured filtering. | "Which universities in Germany have an acceptance rate below 20%, and what is their average tuition fee?" | Decompose the query: Retrieve relevant data (university profiles), and then perform a calculation (average tuition fee) on the subset of retrieved documents. |

Design methodology: Template-based expansion

The main focus of this blog is on retrieval queries. However, unlike standard approaches that simply ask an LLM to rewrite or completely rephrase a query, we adopted a template-based design methodology.

Improving query-text-to-query-text relevance by completely rephrasing the query is often not straightforward for vector nor lexical search. It introduces the complexity of merging search results when multiple hypotheses are considered, and the LLM can often drift from the original user intent. Instead, we explore expanding the original query through an Elasticsearch Query DSL template + prompt strategy. By using specific prompts, we guide the LLM to output specific textual elements (like a list of entities, synonyms, or a pseudo-answer) rather than giving it free rein. These elements are then plugged into a predefined Elasticsearch Query DSL template (a search "recipe").

This approach reduces the scope of the LLM application, making the output more deterministic. In our experiments, the LLM is simply prompted to output some text, which then is inserted into the template.

To validate this approach, we performed a limited exploration of different Elasticsearch primitives to identify and "freeze" a good-enough search template. This allowed us to test how different prompting strategies affect relevance within that fixed structure, rather than changing the structure itself.

While this blog focuses on retrieval queries, and lexical extraction and semantic expansion strategies where the linguistic aspect plays the major role, this methodology is flexible. Specific templates could be designed for other specific retrieval query use cases, such as handling product codes since relevance criteria are often context dependent. However, use cases with queries dependent on complex aggregations or strict filtering should be considered computational queries, which would require query optimization strategies outside the scope of this blog.

Query optimization strategies

While query optimization predates LLMs, LLMs excel at this task. They can be prompted to apply several rewriting strategies [9], such as:

- Generic query rephrasing.

- Pseudo-answer generation.

- Noise reduction (removing irrelevant text, extracting important entities).

- Entity enrichment (synonyms, abbreviation expansion, or other related terms).

- Fixing typos.

- A combination of the above.

Most of these techniques depend on the model’s capacity to understand user intent and its knowledge of the corpus characteristics.

In the following sections, we’ll present our experimentation with query rewriting for informational queries and their application to Elasticsearch. We’ll present our most successful experiments and discuss our unsuccessful ones.

Experiments and results

All the experiments presented in this blog were run using Anthropic Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) at position 10 and Recall at positions 10 and 50 are the metrics used to evaluate the experiments throughout the blog. All NDCG and recall scores were computed using pytrec_eval [10].

We experimented with several variations of the query rewriting task for informational queries and measured relevance and recall gains for three widely used information retrieval benchmarks: Benchmarking Information Retrieval - BEIR, 15 datasets, English-only [11]. Multilingual Document Ranking - MLDR, 13 languages [12] and Multilingual Information Retrieval Across a Continuum of Languages - MIRACL, 18 languages [13].

We mainly explored the following tasks:

- Lexical keyword enrichment.

- Pseudo-answer generation.

- Letting the model decide on a method or a combination of methods among keyword extraction, keyword enrichment, and pseudo-answer generation.

We detail the prompts we used for each case and expand on some attempted variations below.

It’s worth noting that, out of the datasets we evaluated, only four within BEIR (NQ, Robust04, Quora, and MS MARCO) contain real user queries that can benefit from generic query rewriting strategy fixes, such as misspellings, corrections, or query cleaning. The rest of the datasets are either synthetically generated (MLDR, MIRACL) or human-constructed (most of the BEIR datasets).

Lexical keyword enrichment

This is the first task we tried and considered various prompts in an effort to optimize results. We started from the simplest possible version, prompting the LLM to extract relevant keywords without specifying more details.

Prompt 1.

On a second attempt, we tried a prompt with more explicit instructions, prompting the model to provide only the most important keywords, and insisting on why that is important for our use case. We also introduce here the idea of entity enrichment, prompting the model to augment the original query only if it considers it to be too small or missing information.

Prompt 2.

Finally, we tried a prompt with even more explicit instructions and details encouraging the model to apply different techniques based on the original query’s length.

Prompt 3.

We ran lexical search tests on the three prompt variations on a subset of BEIR datasets and compared performance in terms of relevance and recall. The following table lists averaged results over datasets ArguAna, FiQA-2018, Natural Questions (NQ), SciDocs, SciFact, TREC-COVID, Touché 2020, NFCorpus, Robust04:

| Original query | Prompt 1 | Prompt 2 | Prompt 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDCG@10 | 0.346 | 0.345 | 0.356 | 0.346 |

| Recall@10 | 0.454 | 0.453 | 0.466 | 0.455 |

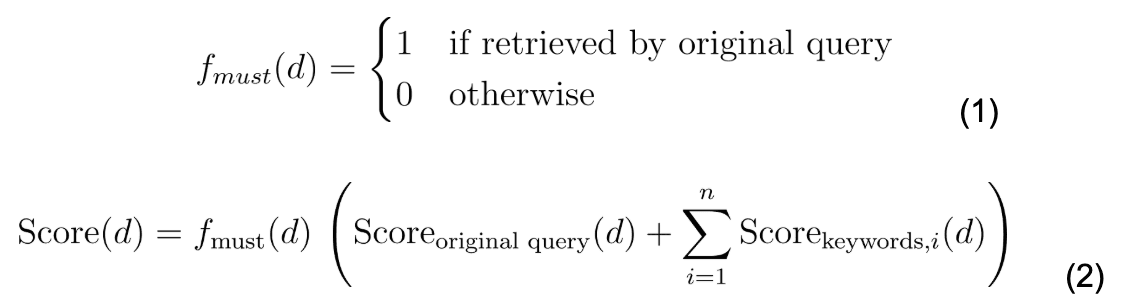

We consider a baseline lexical search of the original queries and compare with experiments where the LLM-output entities are used in lexical search. The results are linearly combined with an Elasticsearch bool query with a must clause wrapping the original query and a should clause for each returned LLM term. (See the Elasticsearch docs for more information on Boolean queries.) The linear combination can be expressed as:

Where n is the number of keywords returned for each query. Score in this case refers to a lexical BM25 score. The query is written in native Elasticsearch Query DSL and is provided in the following section.

The rescoring, including the contribution of the extracted keywords, was applied to the top 200 retrieved documents.

Prompt 2 performs best, both in terms of relevance and recall considering the top 10 results, improving +1pt, whereas the other prompts have little effect. We kept prompt 2 for lexical keyword extraction going forward.

We visually inspect the returned keywords for some of the tested queries in these following examples, and identify several query optimization techniques that were mentioned in the previous section.

Typo corrections:

- Query: when does season 3 of strnger things come out

- Keywords: Stranger Things, Season 3

Noise reduction:

- Query: Evolvability : What Is It and How Do We Get It?

- Keywords: evolvability

Keyword expansion/augmentation:

a)

- Query: Trust-Aware Review Spam Detection

- Keywords: Trust-Aware, Review Spam Detection, fake reviews, credibility

b)

- Query: Dimensional inconsistencies in code and ROS messages: A study of 5.9M lines of code

- Keywords: dimensional inconsistencies, code, ROS, Robot Operating System, 5.9M

c)

- Query: low-carb diets

- Keywords: low-carb, diets, ketogenic, keto, carbohydrate

Pseudo-answer generation

Prompting the LLM to generate pseudo-answers to the original query is another technique that was explored. It has been explored before in the context of query rewriting,9 and is expected to especially benefit factual queries and match the advantages of keyword augmentation. For this method we used the prompt:

Prompt 4.

We explore some examples of LLM outputs for this prompting strategy. For comparison, the extracted Entities for Prompt 4 are also listed.

Providing replies to a general knowledge question:

Query: What is the best way to practice web development?

- Replies:

- Learn HTML, CSS, and JavaScript fundamentals

- Build personal projects and create a portfolio

- Contribute to open-source projects on GitHub

- Follow online tutorials and take coding courses

- Practice responsive design and cross-browser compatibility

- Entities (Prompt 4): development, practice, coding projects, tools

Offering imagined document titles that might contain a reply to a question that cannot be answered based on general knowledge:

Query: In your opinion, what is the best classical song of all time?

- Replies:

- Best classical compositions ranked by music critics

- Most popular and influential classical pieces in history

- Timeless masterpieces from renowned classical composers

- Iconic classical works that have stood the test of time

- Top classical music recommendations for beginners and enthusiasts

- Entities (Prompt 4): classical music, classical composition, symphony, concerto, opera

Query: A description of the history and meaning of the 1st amendment

- Replies:

- First Amendment: origins, historical context, and significance in US Constitution

- Freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly: core principles of 1st Amendment

- Supreme Court interpretations and landmark cases on First Amendment rights

- Evolution of First Amendment protections throughout American history

- Impact and controversies surrounding the First Amendment in modern society

- Entities (Prompt 4): Amendment, Constitution, Bill of Rights

We observe an interesting combination of LLM output modes for this strategy. Different types of queries are handled differently:

- When the query can be directly replied to based on general knowledge, the LLM returns possible replies.

- If not, the LLM “imagines” what the type of document that the user might want could look like and returns these title-like document descriptions as replies.

Both methods end up introducing useful and creative new keywords.

Letting the model choose a method

Finally, experiments were run using a prompt that encouraged the model to select the most appropriate method, or combination of methods and asked it to explain its rationale behind the choice. We expect the model to be inherently capable of “thinking” through how each query can be improved in a search context:

Prompt 5.

The query rewriting implementation for prompts 4 and 5 closely resembles that of prompt 2. Specifically, the LLM output is incorporated into a Boolean query, where the original query is placed in a must clause and each LLM-generated term is included in a should clause. For prompt 4, an LLM-output term represents a single pseudo-answer, while for prompt 5, it represents a rewrite.

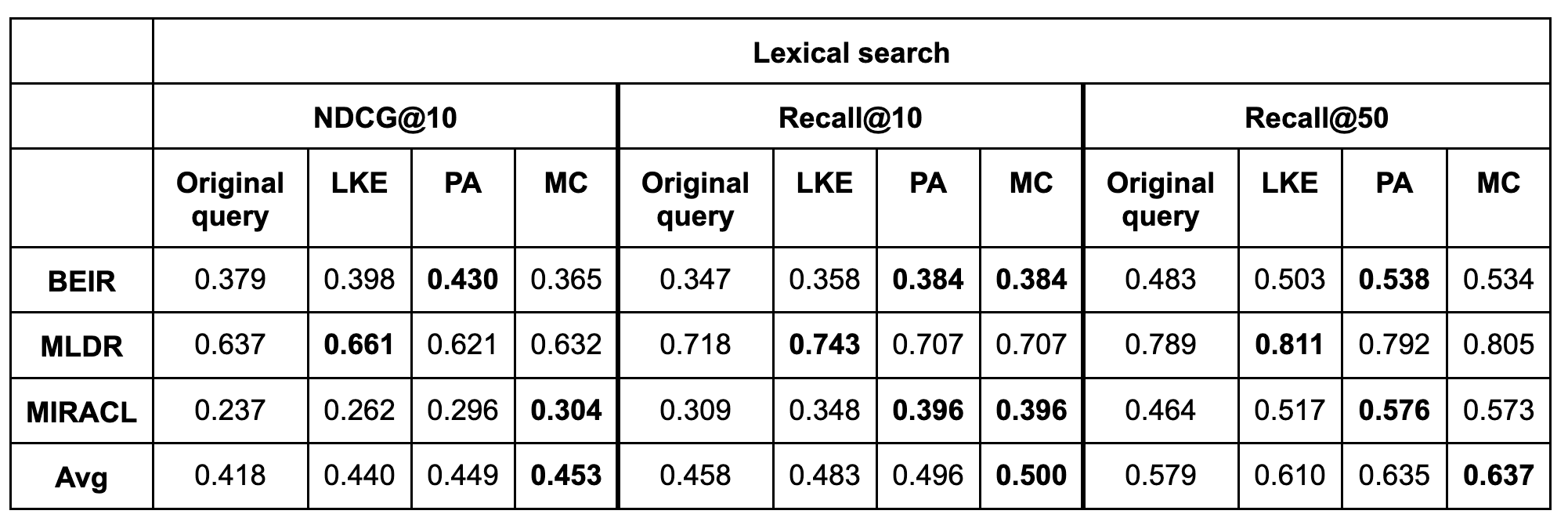

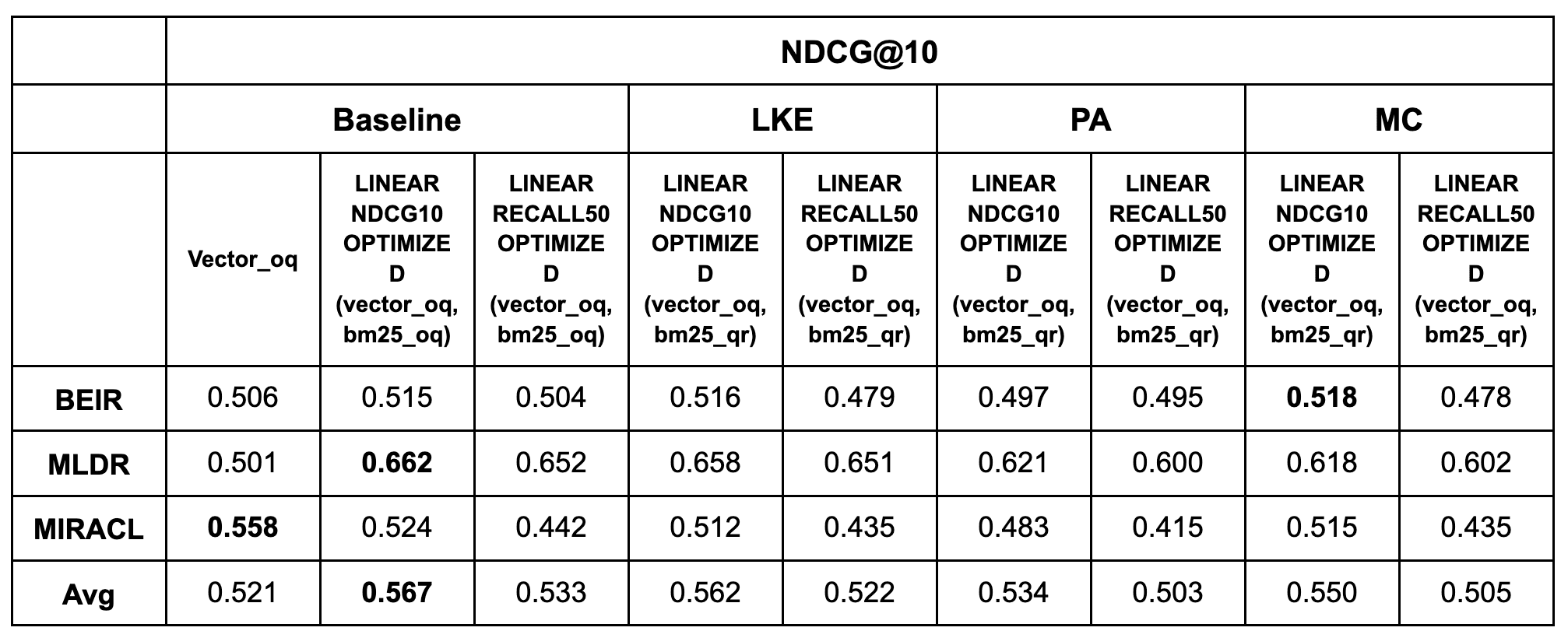

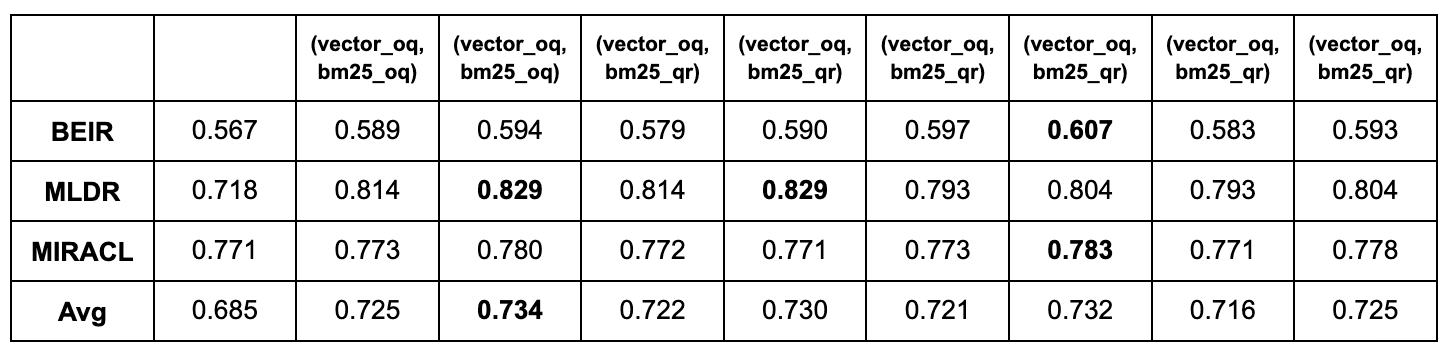

Overall, the change in performance using different prompts is significant in the context of lexical search, where prompts 4 and 5 outperform prompt 2. In the following table, LKE refers to lexical keyword extraction using prompt 2, PA refers to pseudo-answer generation using prompt 4, and MC stands for model’s choice and refers to prompt 5. The model’s output is used according to equation 1.

In the final row of the table, the scores are averaged at the benchmark level. It’s computed as an average of the average scores of BEIR, MLDR, and MIRACL benchmarks. The pseudo-answers and model’s choice strategies perform better across metrics, with pseudo-answers being slightly better.

We further analyze these prompting techniques and obtain more results in the following section, with respect to vector search experiments.

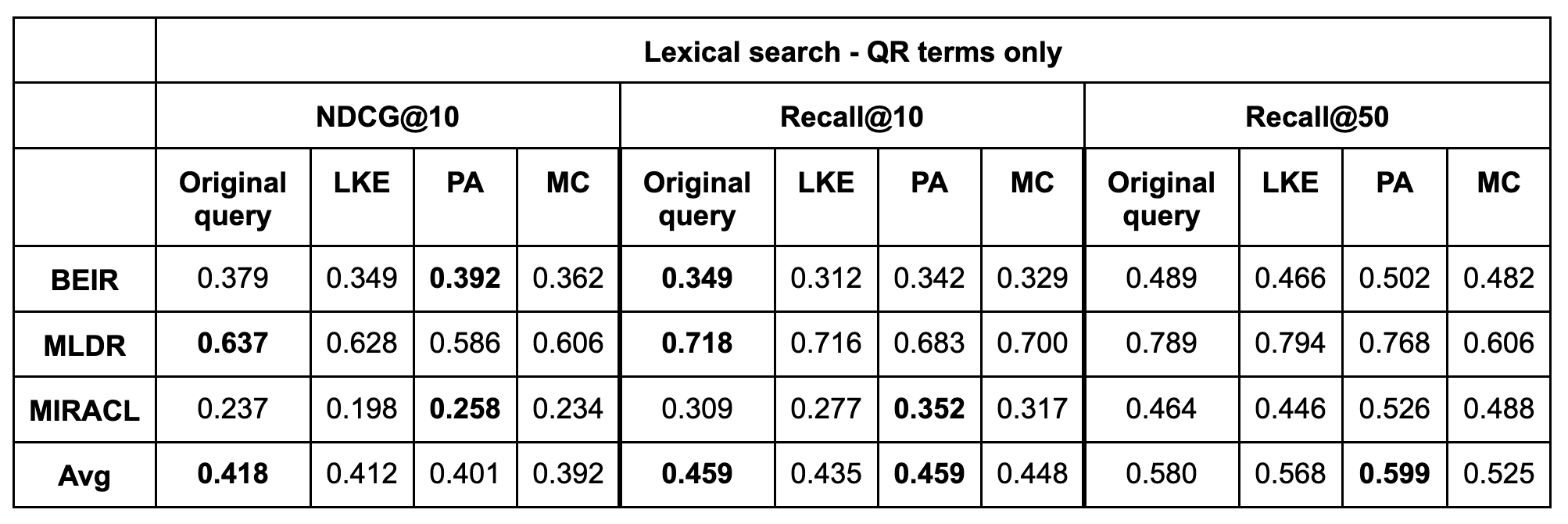

We also present the results of lexical search when using only the query rewriting terms. In the table below, the original query's contribution to the scores is entirely excluded:

Excluding the original query scores from the result seems to hurt relevance performance by average. In terms of Recall@50, the pseudo-answer strategy results in improved performance compared to baseline, but the boost is smaller than when the strategy includes the original query.

Overall, we recommend combining the query rewriting terms with the original query to achieve gains across metrics in lexical search.

Large language models versus small language models

For the majority of the results discussed in this blog, we utilized Anthropic's Claude 3.5 Sonnet LLM. However, we also experimented with a smaller model to assess how inference cost affects performance. We tried LKE with Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Haiku for a subset of datasets from BEIR (ArguAna, FiQA-2018, Natural Questions [NQ], SciDocs, SciFact, TREC-COVID, Touché 2020, NFCorpus, Robust04).

| Original query | LKE with Sonnet | LKE with Haiku | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDCG@10 | 0.346 | 0.364 | 0.368 |

| Recall@10 | 0.454 | 0.472 | 0.475 |

Relevance and recall within the top 10 results remain unaffected. While this initial investigation is not exhaustive and requires further study in real-world scenarios that implement query optimization, these first results strongly suggest that small language models (SLMs) are likely a viable option for this specific use case.

A comparison between Claude 3.5 Sonnet and Claude 3.5 Haiku is provided below:

| Model | Number of parameters | Context window | Max output | Input cost | Output cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet | Est. ~175B | 200K | 8192 tokens | $15.00 / million tokens | $4.00 / million tokens |

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | Est. ~20B | 200K | 8192 tokens | $3.00 / million tokens | $0.80 / million tokens |

Query rewriting in Elasticsearch

In enterprise search, where precision and control are paramount, we explored methods that integrate query rewriting with existing search functionality. The focus was on strategies that build upon the original query to target relevance gains without a high implementation cost.

Elasticsearch features a wide range of search tools that tackle different search scenarios. It supports lexical and vector retrieval, as well as rerankers. We look for optimal ways to integrate query rewriting strategies in Elasticsearch, trying to explore across base retrievers and hybrid methods.

In the previous section, we presented results on lexical search and introduced equations 1 and 2. These correspond to the following Elasticsearch Query DSL code:

QR TERM 1, 2, 3 stands for query rewriting term and refers to whatever the LLM output represents: keywords, pseudo-answers, or other types of replies.

The bool query functions like a linear combination of terms. Crucially, the must clause enforces hard requirements, meaning any document that fails to match this clause is excluded from the results. In contrast, the should clause operates as a score booster: Documents matching it receive a higher final score, but documents that don't match are not discarded from the results.

Through iterative experimentation, we determined the most effective query configuration. Initial attempts included querying solely with terms generated by the LLM or various combinations of the original query and LLM terms. We observed that overreliance on LLM output reduced relevance. The optimal setup, which consistently yielded the best results, required the full inclusion of the original query, with the LLM output used only to selectively boost the ranking of certain documents.

Dense vector search as base retriever

When moving to vector search, the narrative changes. It’s already well-established in the industry that hybrid search (lexical + vector) improves both relevance and recall by combining the semantic understanding of dense vectors with the exact matching precision of BM25. Our goal here was to determine whether query rewriting applied to a vector retriever covers the same gap that hybrid search fixes or provides additional improvement.

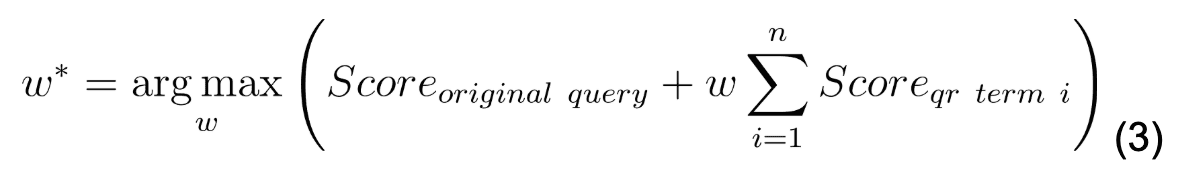

For experiments where the base retriever was not BM25 but rather a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) search using dense vectors, we chose to explore the maximum gains we can achieve in terms of relevance and recall using an optimized, weighted linear combination. We opted to optimize the weight to ensure that the impact of query rewriting strategies on performance is isolated, preventing any potential influence from a poorly chosen linear combination on the results. We run an optimization process expressed in equation 3 using Bayesian Optimization (Optuna14) on the test set itself.

The optimization process was conducted on the same text queries used for evaluation to establish the upper bounds of potential performance improvements. Because we’re tuning only one parameter, the chance of fitting the test data is minimal. We verify this hypothesis below by running the optimization for some datasets on the train split and observe the difference in terms of performance.

For vector search evaluation, we use two optimization metrics:

- LINEAR NDCG@10 OPTIMIZED(vector_oq, bm25_qr): The weight is optimized to achieve the maximum NDCG at the top 10 results.

- LINEAR RECALL@50 OPTIMIZED(vector_oq, bm25_qr): The weight is optimized to achieve the maximum recall at the top 50 results.

In these metrics, oq stands for the original query, and qr stands for query rewriting. We include recall at 50 to assess query optimization's performance as a first-stage retriever, with the assumption that the search results will subsequently be processed by a reranker.

To provide a comparison, we also conducted experiments where the BM25 scores of the original query were combined with the vector search scores. These combinations are referred to as:

- LINEAR NDCG@10 OPTIMIZED(vector_oq, bm25_oq)

- LINEAR RECALL@50 OPTIMIZED(vector_oq, bm25_qr)

For the experiments in the following tables we used the multilingual-e5-large [15] dense vector model for benchmarks BEIR and MIRACL, and the Qwen3-0.6B-Embedding [16] model to search for long-context documents in the MLDR benchmark.

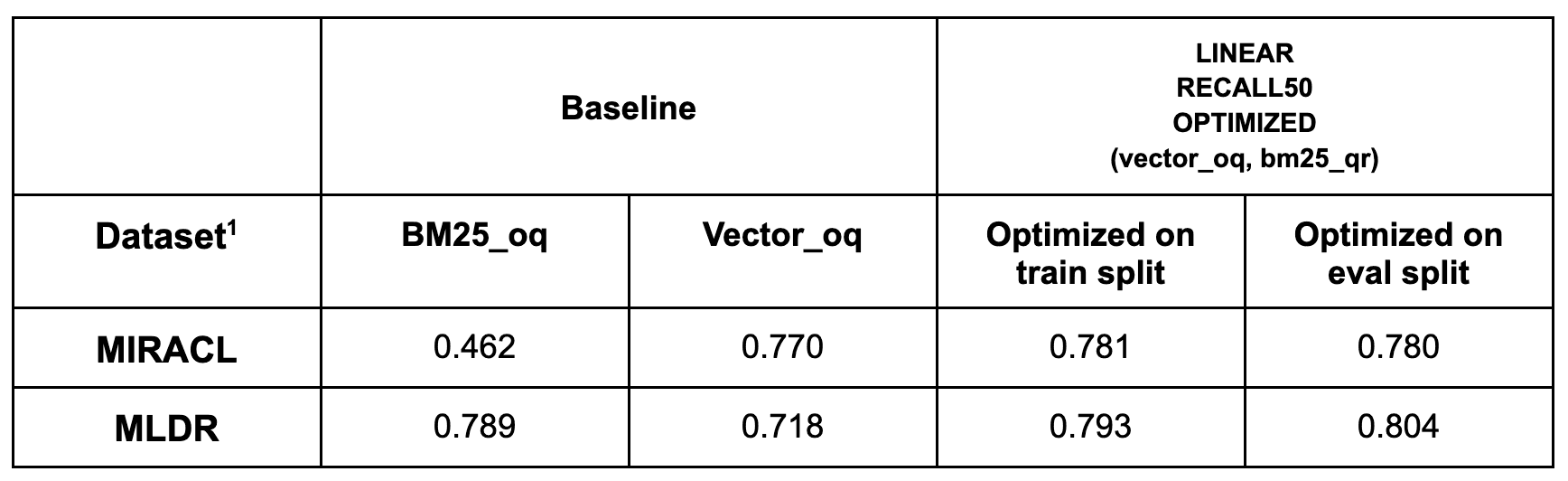

First, we verify that performing the optimization on the evaluation split instead of the training split yields results that follow the same trends. The pseudo-answers prompting strategy was used to compute the qr scores.

We compare the recall@50 scores when optimizing on the training split versus the evaluation split for MIRACL and MLDR, finding that both produced results on the same range.

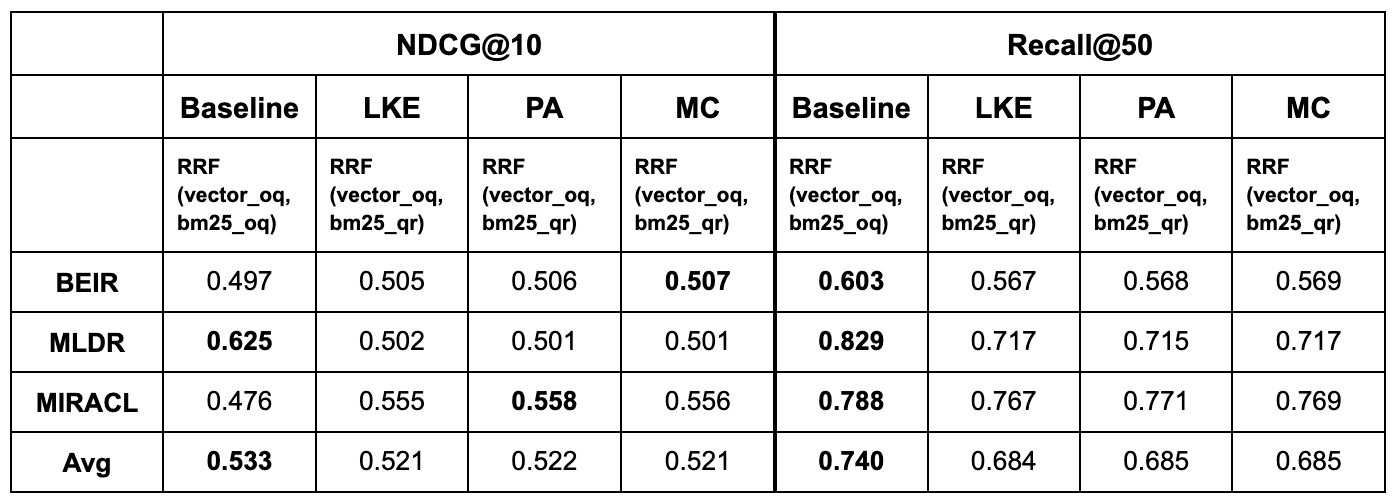

In the following tables, the evaluation split is used for optimization. The final row contains results that are averaged on the benchmark level as in the previous tables.

For the full MLDR dataset, we compared optimizing on the training split versus the test split. For MIRACL, we used the 16 languages with training splits and compared the training split versus the development split (which serves as the common evaluation benchmark since the test set lacks public labels). We did not include BEIR because many of its datasets lack training splits and are meant only for evaluation.

We omit the Recall@10 results as they are very similar to NDCG@10 results. These tables show no advantage in hybrid search using QR terms instead of the original query. In terms of relevance, replacing the original query with QR seems to deteriorate results. In terms of recall, some gains are achieved in BEIR and MIRACL, but the averaged score reveals no advantage over a well-tuned hybrid search.

We further explored hybrid search using reciprocal rank fusion (RRF), relying on the built-in Elasticsearch functionality. Method RRF(vector_oq, bm25_qr) refers to DSL code:

The corresponding baseline run is denoted RRF(vector_oq, bm25_oq).

Replacing the original query with LLM-output terms to get lexical search scores deteriorates recall by average in all cases. In terms of relevance, we observe marginal improvement in BEIR and a notable increase by ~8 points of NDCG@10 in MIRACL. Relevance in MLDR is however so negatively affected that the average result is overall higher in baseline runs.

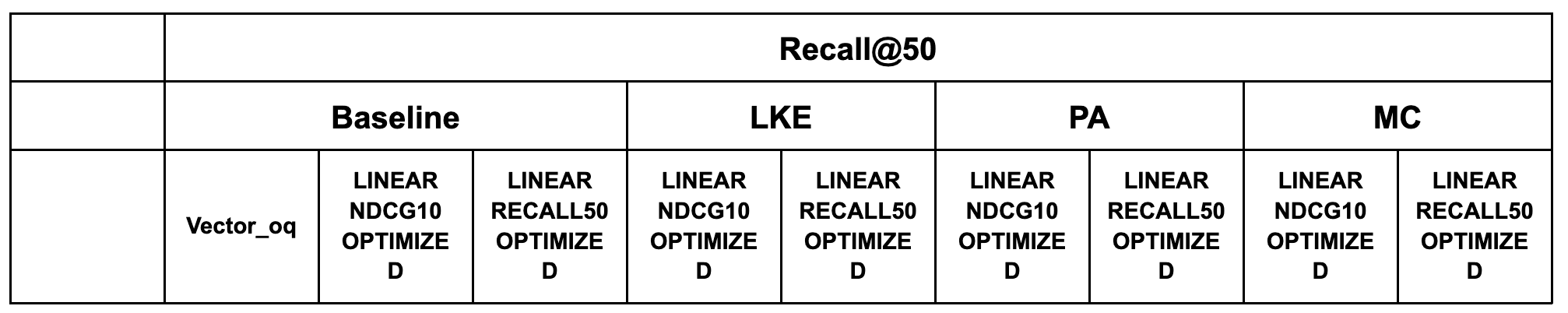

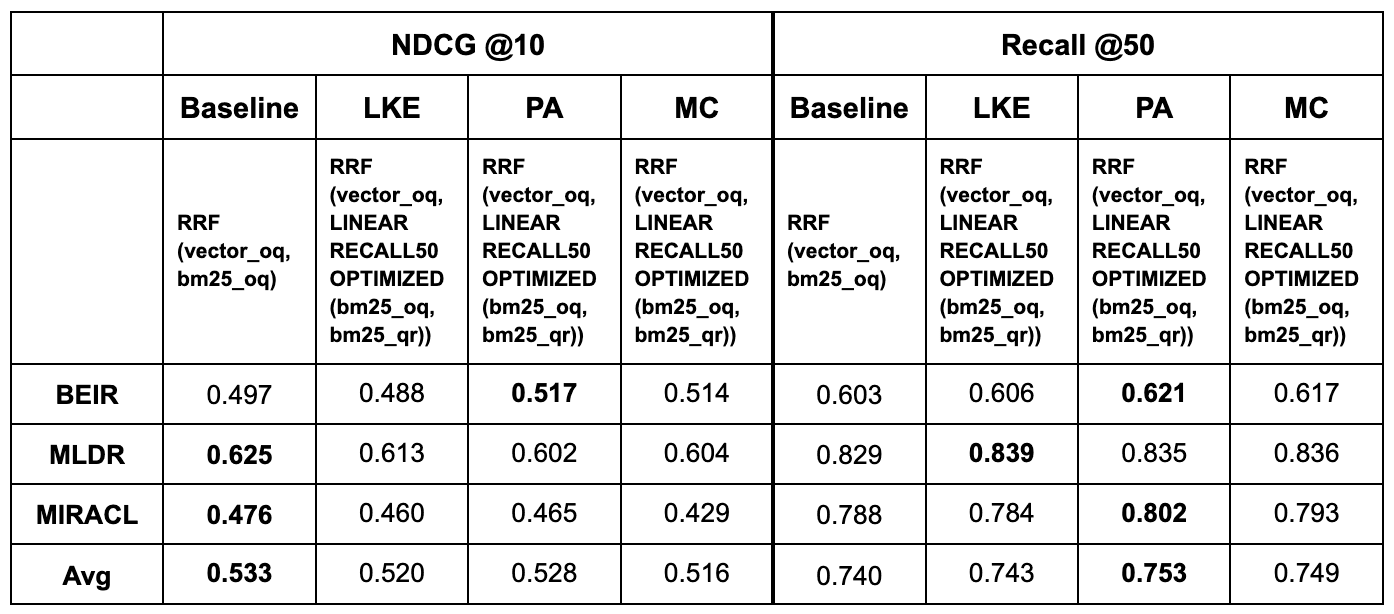

So far, our exploration has not revealed a definitive strategy for enhancing vector search performance through the exposed query rewriting methods. Considering the learnings from the exploration of lexical search, we try experimenting with hybrid search strategies that include both the original query and the query rewriting terms. We focus on a first-stage retrieval scenario and aim to improve Recall@50. In the following experiment, we try hybrid search with RRF, where the lexical scores are computed as an optimized linear combination of BM25 scores of the original query and BM25 scores of LLM-output terms. To establish an upper-bound for potential performance improvements, we perform Bayesian optimization on the set of queries using the Optuna library [14].

We denote this experiment RRF(vector_oq, LINEAR RECALL50 OPTIMIZED(bm25_oq, bm25_qr)). The same baseline as run in the previous table, RRF(vector_oq, bm25_oq), still provides a useful comparison in this experiment.

This experiment was not designed for relevance optimization; however, the resulting NDCG@10 scores are documented for completeness. A 1–3 percentage points of recall@50 increase was achieved with this method, with the prompting strategy that generates pseudo-answers being the most prevalently beneficial among the benchmarks. This strategy is suitable only for informational queries based on general knowledge or when the LLM possesses the necessary domain expertise. This method was employed to determine the upper limits of potential performance improvements. It's important to note that optimizing the weights using the complete test dataset, as was done, is not feasible in real-world applications.

PA turns out to be the most successful strategy for BEIR and MIRACL, while LKE gives the highest boost in recall for MLDR.

First-stage retriever and reranking

To maximize performance in a production setting, query rewriting could be viewed as part of a multistage pipeline. The goal of the first-stage retriever is not to be good at relevance but rather at recall, that is, to ensure the good documents make it into the candidate set for the reranker.

We implemented the following pipeline configuration:

- Base retrieval: Retrieve top 200 documents.

- Entity boosting: Rescore based on LLM-extracted entities (from prompt 2).

- Pruning: Cut to the top 50 documents.

- Reranking: Apply

jina-reranker-v2to the top 50 documents.

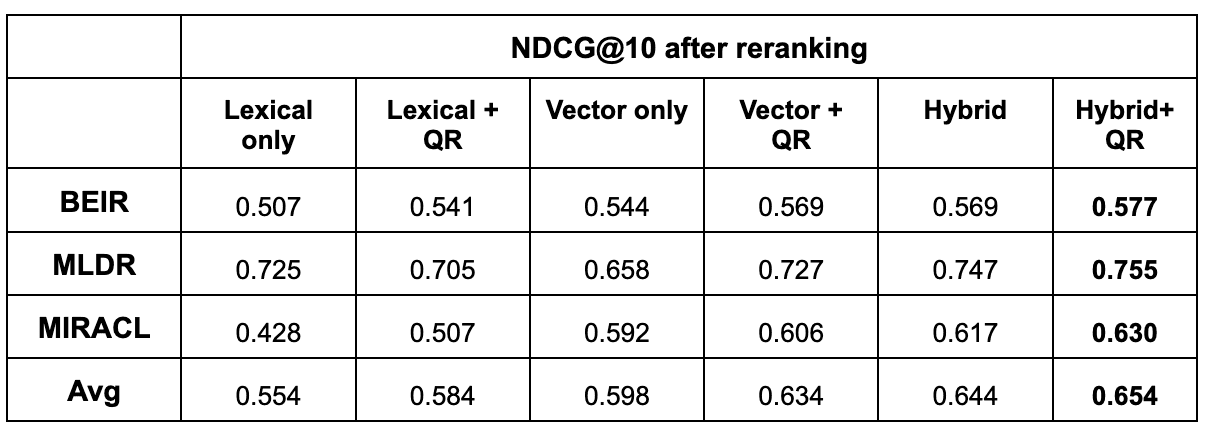

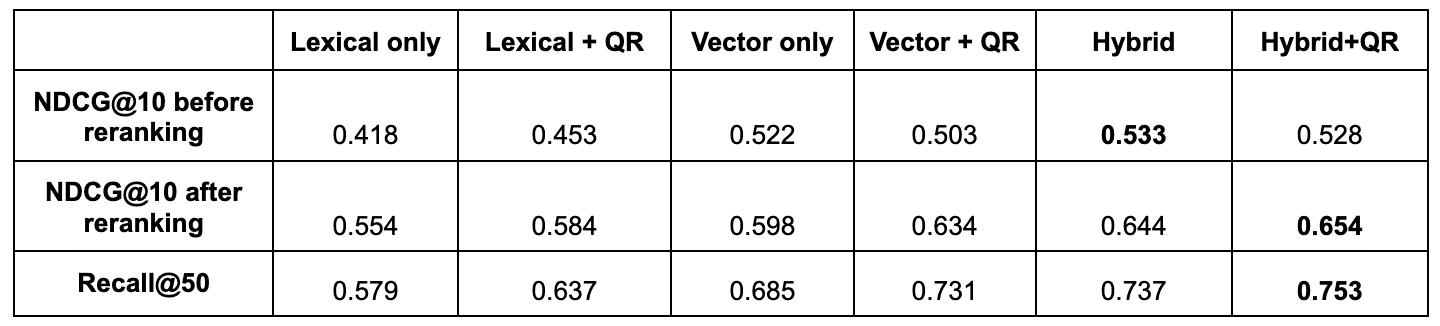

We compared the final outcomes of this pipeline using different first-stage inputs including base retrievers and base retrievers plus QR. For QR and hybrid baseline, we used the experiments that obtained higher recall.

- Lexical corresponds to the original query using BM25.

- Lexical + QR corresponds to the experiment using prompt MC.

- Vector corresponds to the original query using vector search.

- Vector + QR corresponds to the experiment LINEAR RECALL50 OPTIMIZED (vector_oq, bm25_qr) for prompt PA.

- Hybrid corresponds to the RRF (vector_oq, bm25_oq).

Hybrid + QR corresponds to the experiment RRF (vector_oq, LINEAR RECALL50 OPTIMIZED (bm25_oq, bm25_qr)) for prompt PA.

The last row shows the averaged results across BEIR, MLDR, and MIRACL.

QR in lexical and vector is applied by combining the scores as shown in equations (1, 2) and optimized for recall. RRF is widely considered a strong standard for maximizing recall in hybrid search. Our results show that an optimized linear combination of the original vector and QR actually can achieve better recall than the RRF configurations, which cannot be optimized. This suggests that, with the right weighting, a linear combination can be more effective at using LLM-generated queries for recall than rank-based fusion, since optimizing RRF is less effective.

The table below shows the averages across datasets for NDCG@10 before and after reranking and recall@50:

Relevance (NDCG@10) results improve after reranking is applied. Consistently improving alongside recall@50.

Strategy domain adaptation

Unlike open web search, enterprise domains (such as legal, medical, or internal wikis) have specific vocabularies that generic LLMs might miss. Below we discuss several strategies that could be used to tailor the presented QR strategies for specific domains:

- Domain-specific tuning: Further tune the query rewriting instructions (prompts) specifically for niche domains or specific use cases.

- In-context learning: Use few-shot examples retrieved from a knowledge base (such as, append the top k BM25 results to the prompt from a quick, cheap initial search) to ground the rewriting process.

- LLMs + rules hybrid approach: Combine the flexibility of LLMs with deterministic rules for specific domain terms.

- Gated query rewriting: Selectively apply QR only when necessary, employing rules, custom classifiers, or specialized prompts and models to detect whether the query requires optimization for a specific use case

- Generation: Query rewriting for generation: Expanding the query or context not just for retrieval but also specifically to improve the quality of the final LLM response generation.

Conclusions

The investigation shows how simple LLM-driven query optimization can have a positive impact within the modern search ecosystem.

Key take-aways

- LLMs are a good complement to improve lexical search: Using LLMs to enrich keywords or generate pseudo-answers provides consistent improvements in both relevance and recall for standard lexical retrieval.

- Hybrid search is harder to beat: When using dense vector search or hybrid retrieval, simple query rewriting terms offer marginal gains. The best results come from using QR to boost existing hybrid scores rather than replacing them.

- Pseudo-answers improve recall: Generating hypothetical answers (pseudo-answer generation) proved to be the most effective strategy for maximizing recall in multistage pipelines.

- Structured guidance over free-form generation: Guiding the LLM is critical. Rather than allowing the LLM to freely rephrase a query, providing a strict template (like extracting specific entities to fit a DSL clause) ensures that the output adds value without introducing noise. A specific prompt + DSL template combination allows the design for a specific relevance use case (such as lexical extraction versus semantic expansion) and reduces the scope of error.

- Efficiency with small models: The strategies explored here are simple strategies that could be deployed effectively using SLMs or distilled into compact models, offering a cost-effective solution.

The following table contains some practical guidelines on how to incorporate the most successful query rewriting techniques into your search pipeline, depending on your particular setting:

| Real-world setting | QR strategy | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical search | Lexical keyword enrichment (prompt 2) | Boost search performance without the cost of migrating to vector search: Use the LLM's output (keywords, entities, synonyms) in an Elasticsearch `should` clause to boost documents that match the expanded terms, while keeping the original query in a `must` clause. Avoid relying solely on QR-generated terms, and use SLMs to reduce costs without compromising QR performance. |

| Multistage retrieval with reranking | Pseudo-answer generation (prompt 4) | In a multistage search system (retriever followed by a reranker), use the pseudo-answers as boosting terms. Use the Elasticsearch `should` +` must` clauses structure as before to retrieve the widest set of potentially relevant documents before passing them to the reranker to score. |

To reiterate our earlier comments, these solutions will benefit scenarios where most queries are retrieval queries, that is, scenarios where relevance does not depend on specific filtering, aggregations, or other types of structure. However, the same template meta strategy can potentially be adapted to such cases.

The value of task‑focused tuning in search pipeline design

One of the broader implications of this investigation is the importance of viewing search pipeline architectures as a set of modular, well‑defined stages where lightweight, task‑focused adjustments can meaningfully improve performance, allowing pipeline components to be tuned for specific retrieval goals. Such tuning could involve a variety of strategies, including experimenting with how LLMs are prompted to target particular gains (such as maximizing recall versus precision), parametrizing how LLM output is combined with the original query (for example, DSL Query template), or evaluating the impact of different rescoring strategies (such as MMR or match_phrase–based query rescoring) on an initial candidate set (such as the top 200 retrieved documents), and layering these techniques before a more computationally intensive reranking step. Overall, this perspective encourages designing pipelines with clear component boundaries and a small, controllable set of hyperparameters that can be tuned to achieve targeted retrieval outcomes. Furthermore, although our experiments demonstrated measurable gains in a general‑purpose IR setting, we expect these interventions to be even more impactful in scenarios where relevance is narrowly defined, allowing the template‑based approach to improve results in a more controlled way.

LLM-driven query optimization in modern search pipelines

Simple query rewriting strategies can be well-suited, easy-to-plug-in solutions for targeted performance gains. In environments where LLMs are already in use (for example, RAG, conversational interfaces, or agentic search workflows), the overhead of an extra LLM call for rewriting is absorbed, making latency less of an issue. This allows for significant and targeted improvements in relevance and recall across specific domains or challenging query types.

All the strategies discussed in this blog consist of a combination of an LLM prompt and an Elasticsearch Query DSL template, and hence they can be naturally integrated into the application layer of a search solution.

Finally, Elasticsearch has already begun integrating LLM-powered capabilities directly into its search experience, offering tools like ES|QL COMPLETION, managed LLMs through the Elastic Inference Service (EIS), and lately, the possibility to build a custom query rewriting tool within Elastic Agent Builder.

A detailed table of the results presented can be found here.

References

- Xiong, H., Bian, J., Li, Y., Li, X., Du, M., Wang, S., Yin, D., & Helal, S. (2024). When search engine services meet large language models: Visions and challenges. arXiv.

- Remmey, M. (2024, May 14). NL to SQL architecture alternatives. Azure Architecture Blog. https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/azurearchitectureblog/nl-to-sql-architecture-alternatives/4136387

- Abdallah, A., Piryani, B., Mozafari, J., Ali, M., & Jatowt, A. (2025, August 22). How good are LLM-based rerankers? An empirical analysis of state-of-the-art reranking models. arXiv. arxiv

- Joshi, A., Shi, Z., Goindani, A., & Liu, H. (2025, October 22). The case against LLMs as rerankers. Voyage AI. https://blog.voyageai.com/2025/10/22/the-case-against-llms-as-rerankers/

- Oosterhuis, H., Jagerman, R., Qin, Z., & Wang, X. (2025, July). Optimizing compound retrieval systems. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’25) (pp. 1–11). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3726302.3730051

- Zhang Y, Li M, Long D, Zhang X, Lin H, Yang B, Xie P, Yang A, Liu D, Lin J, Huang F, Zhou J. Qwen3 Embedding: Advancing Text Embedding and Reranking Through Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05176. 2025. arXiv

- Wang L, Yang N, Huang X, Yang L, Majumder R, Wei F. Improving Text Embeddings with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.00368. 2024. arXiv

- Lee J, Dai Z, Ren X, Chen B, Cer D, Cole JR, et al. Gecko: Versatile Text Embeddings Distilled from Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.20327. 2024. arxiv

- Li, Zhicong; Wang, Jiahao; Jiang, Zhishu; Mao, Hangyu; Chen, Zhongxia; Du, Jiazhen; Zhang, Yuanxing; Zhang, Fuzheng; Zhang, Di; Liu, Yong (2024). DMQR-RAG: Diverse Multi-Query Rewriting for RAG. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.13154. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2411.13154. (arxiv)

- Van Gysel C, de Rijke M. pytrec_eval: An extremely fast Python interface to trec_eval. In: Proceedings of the 2018 SIGIR Workshop on Reproducibility in Information Retrieval; 2018.

- Thakur N, Reimers N, Rücklé A, Srivastava A, Gurevych I. BEIR: A Heterogeneous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval Models. arXiv [cs.IR]. 2021;arXiv:2104.08663. (arxiv)

- Chen J, Xiao S, Zhang P, Luo K, Lian D, Liu Z. BGE M3-Embedding: Multi-Linguality, Multi-Functionality, Multi-Granularity Text Embeddings Through Self-Knowledge Distillation. arXiv [cs.CL]. 2024;arXiv:2402.03216. (arxiv)

- Zhang X, Thakur N, Ogundepo O, Kamalloo E, Alfonso-Hermelo D, Li X, Liu Q, Rezagholizadeh M, Lin J. MIRACL: A Multilingual Retrieval Dataset Covering 18 Diverse Languages. Trans Assoc Comput Linguistics. 2023;11:1114-1131. (aclanthology.org)

- Akiba T, Sano S, Yanase T, Ohta T, Koyama M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD ’19). 2019:2623-2631. doi:10.1145/3292500.3330701

- Wang L, Yang N, Huang X, Yang L, Majumder R, Wei F. Multilingual E5 Text Embeddings: A Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05672. Published 2024. Accessed November 18, 2025. arxiv

- Zhang Y, Li M, Long D, Zhang X, Lin H, Yang B, Xie P, Yang A, Liu D, Lin J, Huang F, Zhou J. Qwen3 Embedding: Advancing Text Embedding and Reranking Through Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05176. Published 2025. Accessed November 18, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.05176 Hugging Face+2GitHub+2