Elasticsearch has native integrations to industry leading Gen AI tools and providers. Check out our webinars on going Beyond RAG Basics, or building prod-ready apps Elastic Vector Database.

To build the best search solutions for your use case, start a free cloud trial or try Elastic on your local machine now.

Jina by Elastic provides search foundation models for applications and business process automation. These models provide core functionality for bringing AI to Elasticsearch applications and innovative AI projects.

Jina models fall into three broad categories designed to support information processing, organization, and retrieval:

- Semantic embedding models

- Reranking models

- Small generative language models

Semantic embedding models

The idea behind semantic embeddings is that an AI model can learn to represent aspects of the meaning of its inputs in terms of the geometry of high-dimensional spaces.

You can think of a semantic embedding as a point (technically a vector) in a high-dimensional space. An embedding model is a neural network that takes some digital data as input (potentially anything, but most often a text or an image) and outputs the location of a corresponding high-dimensional point as a set of numerical coordinates. If the model is good at its job, the distance between two semantic embeddings is proportionate to how much their corresponding digital objects mean the same things.

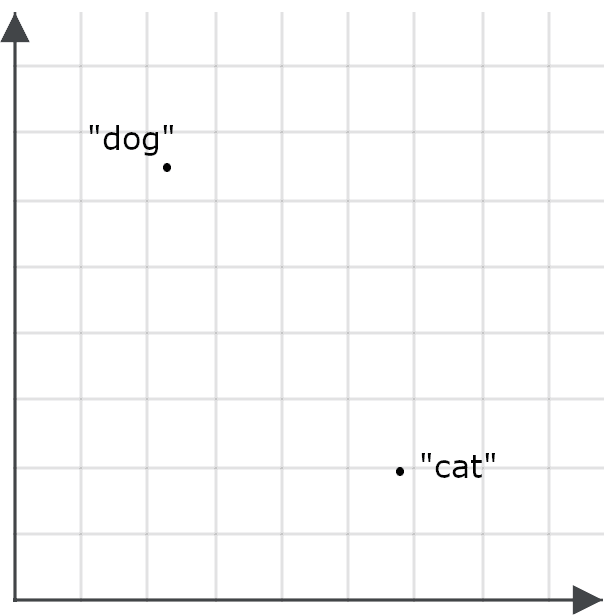

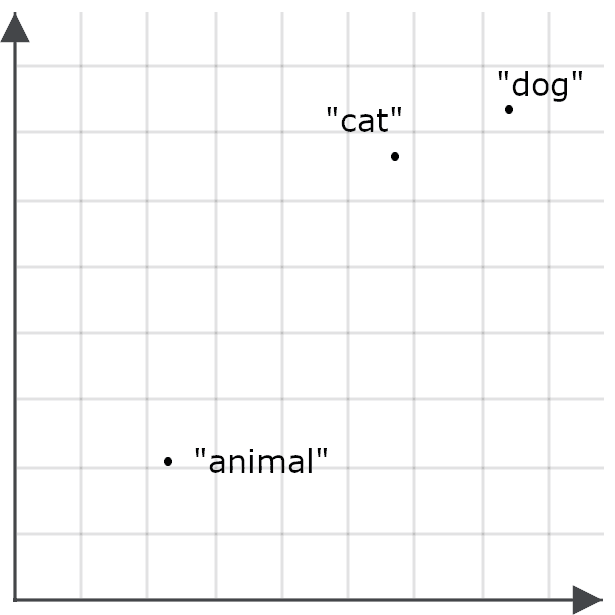

To understand how this is important for search applications, imagine one embedding for the word “dog” and one for the word “cat” as points in space:

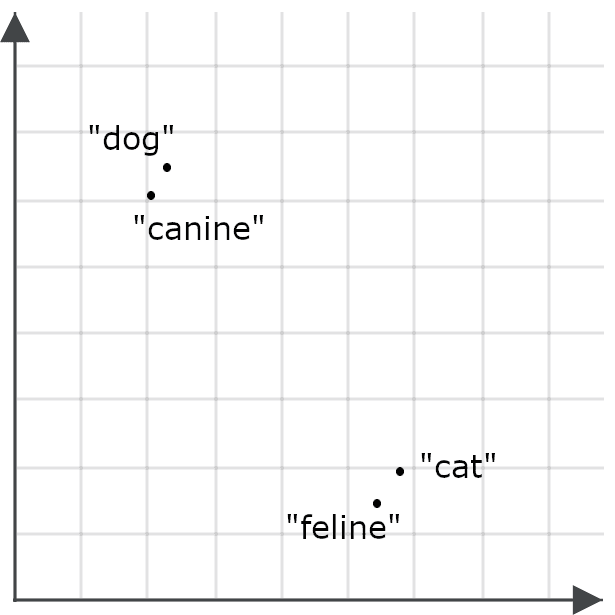

A good embedding model should generate an embedding for the word “feline” that’s much closer to “cat” than to “dog,” and “canine” should have an embedding much closer to “dog” than to “cat,” because those words mean almost the same thing:

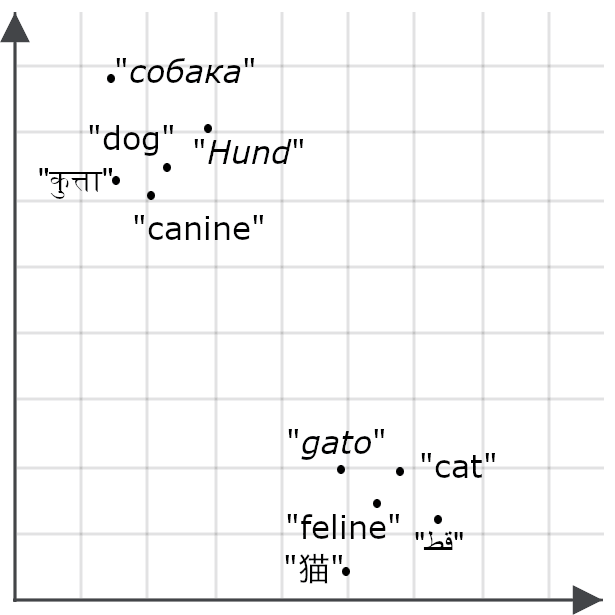

If a model is multilingual, we would expect the same thing for translations of “cat” and “dog”:

Embedding models translate similarity or dissimilarity in meaning between things into spatial relationships between embeddings. The pictures above have just two dimensions so you can see them on a screen, but embedding models produce vectors with dozens to thousands of dimensions. This makes it possible for them to encode subtleties of meaning for whole texts, assigning a point in a space that has hundreds or thousands of dimensions for documents of thousands of words or more.

Multimodal embeddings

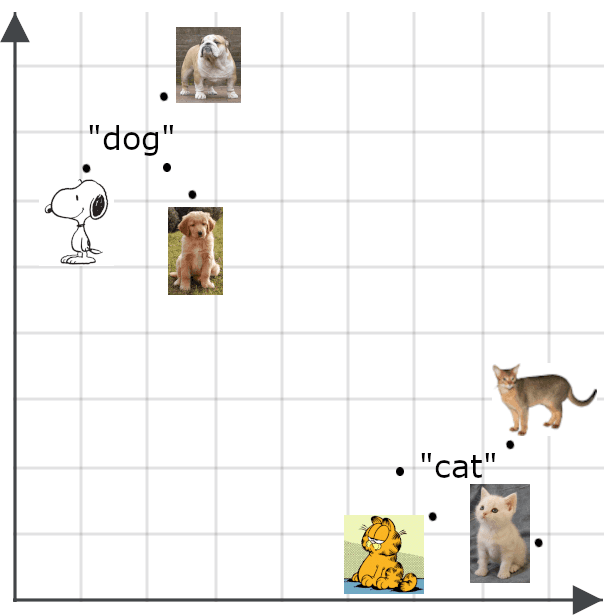

Multimodal models extend the concept of semantic embeddings to things other than texts, especially to images. We would expect an embedding for a picture to be near to an embedding of a faithful description of the picture:

Semantic embeddings have a lot of uses. Among other things, you can use them to build efficient classifiers, to do data clustering, and to accomplish a variety of tasks, like data deduplication and investigating data diversity, both of which are important for big data applications that involve working with too much data to manage by hand.

The biggest direct use of embeddings is in information retrieval. Elasticsearch can store retrieval objects with embeddings as keys. Queries are converted into embedding vectors, and a search returns the stored objects whose keys are the nearest to the query embedding.

Where traditional vector-based retrieval (sometimes called sparse vector retrieval) uses vectors based on words or metadata in documents and queries, embedding-based retrieval (also known as dense vector retrieval) uses AI-assessed meanings rather than words. This makes them generally much more flexible and more accurate than traditional search methods.

Matryoshka representation learning

The number of dimensions an embedding has, and the precision of the numbers in it have significant performance impacts. Very high-dimensional spaces and extremely high-precision numbers can represent highly detailed and complex information, but demand larger AI models that are more expensive to train and to run. The vectors they generate require more storage space, and it takes more computing cycles to calculate the distances between them. Using semantic embedding models involves making important trade-offs between precision and resource consumption.

To maximize flexibility for users, Jina models are trained with a technique called Matryoshka Representation Learning. This causes models to front-load the most important semantic distinctions into the first dimensions of the embedding vector so you can just cut off the higher dimensions and still get good performance.

In practice, this means that users of Jina models can choose how many dimensions they want their embeddings to have. Choosing fewer dimensions reduces precision, but the degradation in performance is minor. On most tasks, performance metrics for Jina models decline 1–2% every time you reduce the embedding size by 50%, down to about a 95% reduction in size.

Asymmetric retrieval

Semantic similarity is usually measured symmetrically. The value you get when comparing “cat” to “dog” is the same as the value you’d get comparing “dog” to “cat.” But when you use embeddings for information retrieval, they work better if you break the symmetry and encode queries differently from the way you encode retrieval objects.

This is because of the way we train embedding models. Training data contains instances of the same elements, like words, in many different contexts, and models learn semantics by comparing the contextual similarities and differences between elements.

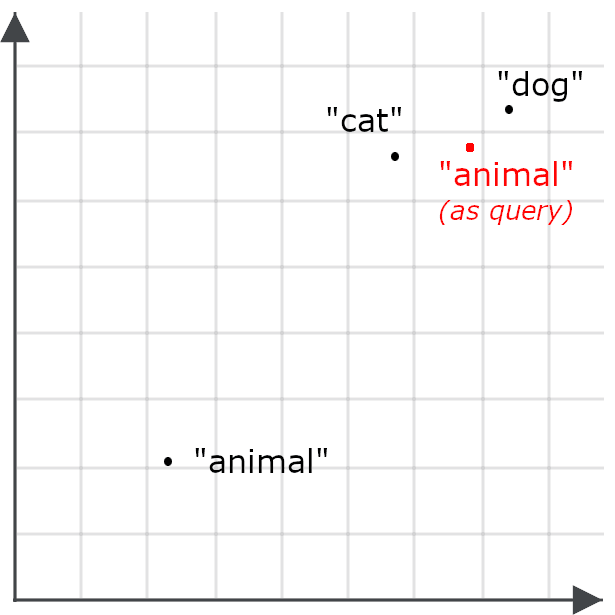

So, for example, we might find that the word “animal” doesn’t appear in very many of the same contexts as “cat” or “dog,” and therefore the embedding for “animal” might not be particularly close to “cat” or “dog”:

This makes it less likely that a query for “animal” will retrieve documents about cats and dogs — the opposite of our goal. So instead, we encode “animal” differently when it’s a query than when it’s a target for retrieval:

Asymmetric retrieval means using a different model for queries or specially training an embedding model to encode things one way when they’re stored for retrieval and to encode queries another way.

Multivector embeddings

Single embeddings are good for information retrieval because they fit the basic framework of an indexed database: We store objects for retrieval with a single embedding vector as their retrieval key. When users query the document store, their queries are translated into embedding vectors and the documents whose keys are closest to the query embedding (in the high-dimensional embedding space) are retrieved as candidate matches.

Multivector embeddings work a little differently. Instead of generating a fixed-length vector to represent a query and a whole stored object, they produce a sequence of embeddings representing smaller parts of them. The parts are typically tokens or words for texts and are image tiles for visual data. These embeddings reflect the meaning of the part in its context.

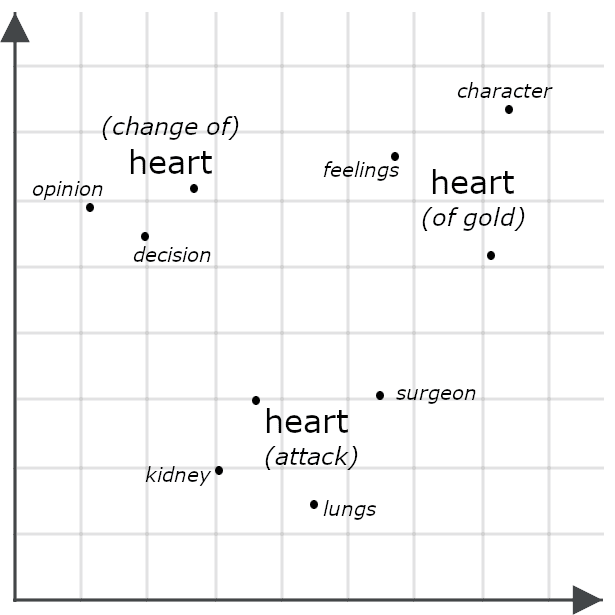

For example, consider these sentences:

- She had a heart of gold.

- She had a change of heart.

- She had a heart attack.

Superficially, they look very similar, but a multivector model would likely generate very different embeddings for each instance of “heart,” representing how each means something else in the context of the whole sentence:

Comparing two objects via their multivector embeddings often involves measuring their chamfer distance: comparing each part of one multivector embedding to each part of another one and summing the minimum distances between them. Other systems, including the Jina Rerankers described below, input them to an AI model trained specifically to evaluate their similarity. Both approaches typically have higher precision than just comparing single-vector embeddings because multivector embeddings contain much more detailed information than single-vector ones.

However, multivector embeddings aren’t well-suited to indexing. They’re often used in reranking tasks, as described for the jina-colbert-v2 model in the next section.

Jina embedding models

Jina embeddings v4

jina-embeddings-v4 is a 3.8 billion (3.8x10⁹) parameter multilingual and multimodal embedding model that supports images and texts in a variety of widely used languages. It uses a novel architecture to take advantage of visual knowledge and language knowledge to improve performance on both tasks, enabling it to excel at image retrieval and especially at visual document retrieval. This means it handles images like charts, slides, maps, screenshots, page scans, and diagrams — common kinds of images, often with important embedded text, which fall outside the scope of computer vision models trained on pictures of real-world scenes.

We’ve optimized this model for several different tasks using compact Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) adapters. This allows us to train a single model to specialize at multiple tasks, without compromising performance on any of them, at a minimal added cost in memory or processing.

Main features include:

- State-of-the-art performance in visual document retrieval, along with multilingual text and regular image performance that surpasses significantly larger models.

- Support for large input context size: 32,768 tokens is roughly equivalent to 80 pages of double-spaced English text, and 20 megapixels is equivalent to an image of 4,500 x 4,500 pixels.

- User-selected embedding sizes, from a maximum of 2048 dimensions down to 128 dimensions. We found empirically that performance degrades dramatically below that threshold.

- Support for both single embeddings and multivector embeddings. For texts, multivector output consists of one 128-dimensional embedding for each input token. For images, it produces one 128-dimensional embedding for each 28x28 pixel tile needed to cover the image.

- Optimization for asymmetric retrieval via a pair of LoRA adapters trained specifically for the purpose.

- A LoRA adapter optimized for semantic similarity calculation.

- Special support for computer programming languages and IT frameworks, also via a LoRA adapter.

We developed jina-embeddings-v4 to serve as a general, multipurpose tool for a broad array of common search, natural language understanding, and AI analysis tasks. It’s a relatively small model given its capabilities but still takes significant resources to deploy and is best suited to use via a cloud API or in a high-volume environment.

Jina embeddings v3

jina-embeddings-v3 is a compact, high-performance, multilingual, text-only embedding model with under 600 million parameters. It supports up to 8192 tokens of text input and outputs single-vector embeddings with user-chosen sizes from a default of 1024 dimensions down to 64.

We’ve trained jina-embeddings-v3 for a variety of text tasks — not just information retrieval and semantic similarity but also classification tasks, like sentiment analysis and content moderation, as well as clustering tasks, like news aggregation and recommendation. Like jina-embeddings-v4, this model provides LoRA adapters specialized for the following categories of usage:

- Asymmetric retrieval

- Semantic similarity

- Classification

- Clustering

jina-embeddings-v3 is a much smaller model than jina-embeddings-v4 with a significantly reduced input context size, but it costs less to operate. Nonetheless, it has very competitive performance, albeit only for texts, and is a better choice for many use cases.

Jina code embeddings

Jina’s specialized code embedding models — jina-code-embeddings (0.5b and 1.5b) — support 15 programming schemes and frameworks, as well as English language texts relating to computing and information technology. They’re compact models with a half-billion (0.5x10⁹) and one-and-a-half-billion (1.5x10⁹) parameters, respectively. Both models support input context sizes of up to 32,768 tokens and let users select their output embedding sizes, from 896 down to 64 dimensions for the smaller model and 1536 down to 128 for the larger.

These models support asymmetric retrieval for five task-specific specializations, using prefix tuning rather than LoRA adapters:

- Code to code. Retrieve similar code across programming languages. This is used for code alignment, code deduplication, and support for porting and refactoring.

- Natural language to code. Retrieve code to match natural language queries, comments, descriptions, and documentation.

- Code to natural language. Match code to documentation or other natural language texts.

- Code-to-code completion. Suggest relevant code to complete or enhance existing code.

- Technical Q&A. Identify natural language answers to questions about information technologies, ideally suited for technical support use cases.

These models provide superior performance for tasks involving computer documentation and programming materials at a relatively small computational cost. They’re well suited to integration into development environments and code assistants.

Jina ColBERT v2

jina-colbert-v2 is a 560 million parameter multivector text-embedding model. It’s multilingual, trained using materials in 89 languages, and supports variable embedding sizes and asymmetric retrieval.

As previously noted, multivector embeddings are poorly suited to indexing but are very useful for increasing the precision of results of other search strategies. Using jina-colbert-v2, you can calculate multivector embeddings in advance and then use them to rerank retrieval candidates at query time. This approach is less precise than using one of the reranking models in the next section but is much more efficient because it just involves comparing stored multivector embeddings instead of invoking the whole AI model for every query and candidate match. It’s ideally suited for use cases where the latency and computational overhead of using reranking models is too great or where the number of candidates to compare is too large for reranking models.

This model outputs a sequence of embeddings, one per input token, and users can select token embeddings of 128-, 96-, or 64-dimension embeddings. Candidate text matches are limited to 8,192 tokens. Queries are encoded asymmetrically, so users must specify whether a text is a query or candidate match and must limit queries to 32 tokens.

Jina CLIP v2

jina-clip-v2 is a 900 million parameter multimodal embedding model, trained so that texts and images produce embeddings that are close together if the text describes the content of the image. Its primary use is for retrieving images based on textural queries, but it’s also a high-performance text-only model, reducing user costs because you don’t need separate models for text-to-text and text-to-image retrieval.

This model supports a text input context of 8,192 tokens, and images are scaled to 512x512 pixels before generating embeddings.

Contrastive language–image pretraining (CLIP) architectures are easy to train and operate and can produce very compact models, but they have some fundamental limitations. They can’t use knowledge from one medium to improve their performance in another. They can’t use from one medium to improve their performance in another. So, although it might know that the words “dog” and “cat” are closer to each other in meaning than either one is to “car,” it won’t necessarily know that a picture of a dog and a picture of a cat are more related than either one is to a picture of a car.

They also suffer from what is called the modality gap: An embedding of a text about dogs is likely to be closer to an embedding of a text about cats than to an embedding of a picture of dogs. Because of this limitation, we advise using CLIP as a text-to-image retrieval model or as a text-only model, but not mixing the two in a single query.

Reranking models

Reranking models take one or more candidate matches, along with a query as input to the model, and compare them directly, producing much higher precision matches.

In principle, you could use a reranker directly for information retrieval by comparing each query to each stored document, but this would be very computationally expensive and is impractical for any but the smallest collections. As a result, rerankers tend to be used to evaluate relatively short lists of candidate matches found by some other means, like embeddings-based search or other retrieval algorithms. Reranking models are ideally suited to hybrid and federated search schemes, where performing a search might mean that queries get sent to separate search systems with distinct data sets, each one returning different results. They work very well at merging diverse results into a single high-quality result.

Embeddings-based search can be a large commitment, involving reindexing all your stored data and changing user expectations about the results. Adding a reranker to an existing search scheme can add many of the benefits of AI without re-engineering your entire search solution.

Jina reranker models

Jina Reranker m0

jina-reranker-m0 is a 2.4 billion (2.4x10⁹) parameter multimodal reranker that supports textual queries and candidate matches consisting of texts and/or images. It’s the leading model for visual document retrieval, making it an ideal solution for stores of PDF, scans of text, screenshots, and other computer-generated or modified imagery containing text or other semistructured information, as well as mixed data consisting of text documents and images.

This model takes a single query and a candidate match and returns a score. When the same query is used with different candidates, the scores are comparable and can be used to rank them. It supports a total input size of up to 10,240 tokens, including the query text and the candidate text or image. Every 28x28 pixel tile needed to cover an image counts as a token for calculating input size.

Jina Reranker v3

jina-reranker-v3 is a 600 million parameter text reranker with state-of-the-art performance for models of comparable size. Unlike jina-reranker-m0, it takes a single query and a list of up to 64 candidate matches and returns the ranking order. It has an input context of 131,000 tokens, including the query and all text candidates.

Jina Reranker v2

jina-reranker-v2-base-multilingual is a very compact general-purpose reranker with additional features designed to support function-calling and SQL querying. Weighing in at under 300 million parameters, it provides fast, efficient, and accurate multilingual text reranking with additional support for selecting SQL tables and external functions that match text queries, making it suitable for agentic use cases.

Small generative language models

Generative language models are models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google Gemini, and Claude from Anthropic that take text or multimedia inputs and respond with text outputs. There’s no well-defined line that separates large language models (LLMs) from small language models (SLMs), but the practical problems of developing, operating, and using top-of-the-line LLMs are well-known. The best-known ones are not publicly distributed, so we can only estimate their size, but ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude are expected to be in the 1–3 trillion (1–3x10¹²) parameter range.

Running these models, even if they’re openly available, is far beyond the scope of conventional hardware, requiring the most advanced chips arranged in vast parallel arrays. You can access LLMs via paid APIs, but this incurs significant costs, has a large latency, and is difficult to align with demands for data protection, digital sovereignty, and cloud repatriation. Additionally, costs related to training and customizing models of that size can be considerable.

Consequently, a great deal of research has gone into developing smaller models that might lack all the capabilities of the largest LLMs but can perform specific kinds of tasks just as well at a reduced cost. Enterprises generally deploy software to address specific problems, and AI software is no different, so SLM-based solutions are often preferable to LLM ones. They can typically run on commodity hardware, are faster and consume less energy to run, and are much easier to customize.

Jina’s SLM offerings are growing as we focus on how we can best bring AI into practical search solutions.

Jina SLMs

ReaderLM v2

ReaderLM-v2 is a generative language model that converts HTML into Markdown or into JSON, according to user-provided JSON schemas and natural language instructions.

Data preprocessing and normalization is an essential part of developing good search solutions for digital data, but real-world data, especially web-derived information, is often chaotic, and simple conversion strategies frequently prove to be very brittle. Instead, ReaderLM-v2 offers an intelligent AI model solution that can understand the chaos of a DOM-tree dump of a web page and robustly identify useful elements.

At 1.5 billion (1.5x10⁹) parameters, it’s three orders of magnitude more compact than cutting-edge LLMs but performs on par with them at this one narrow task.

Jina VLM

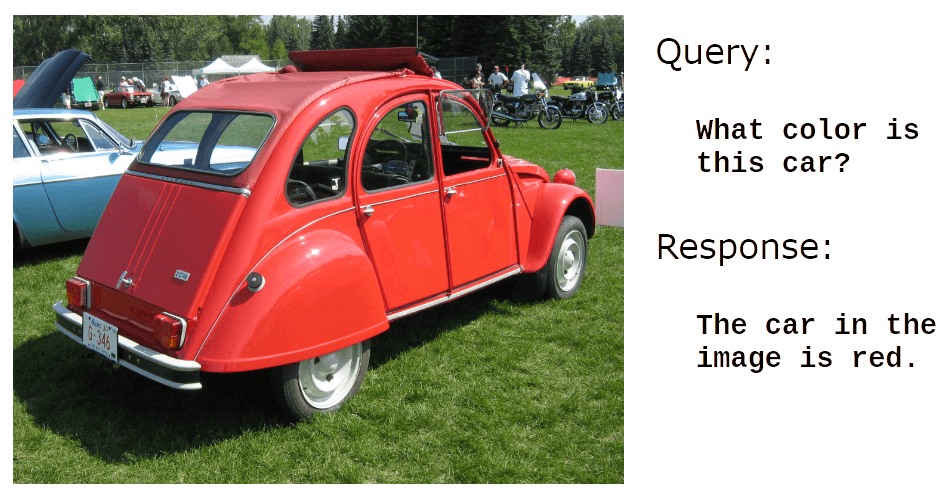

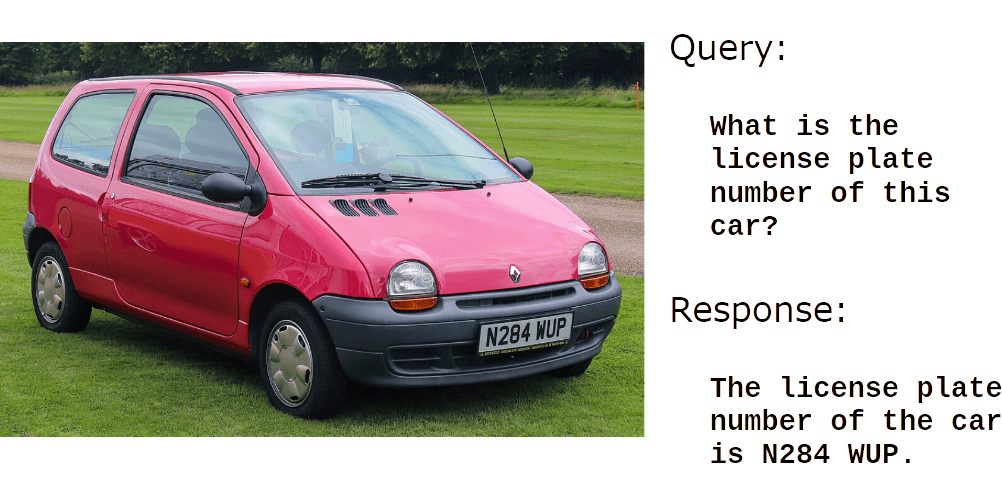

jina-vlm is a 2.4 billion (2.4x10⁹) parameter generative language model trained to answer natural language questions about images. It has very strong support for visual document analysis, that is, answering questions about scans, screenshots, slides, diagrams, and similar non-natural image data.

For example:

Photo credit: User dave_7 at Wikimedia Commons.

It’s also very good at reading text in images:

Photo credit: User Vauxford at Wikimedia Commons.

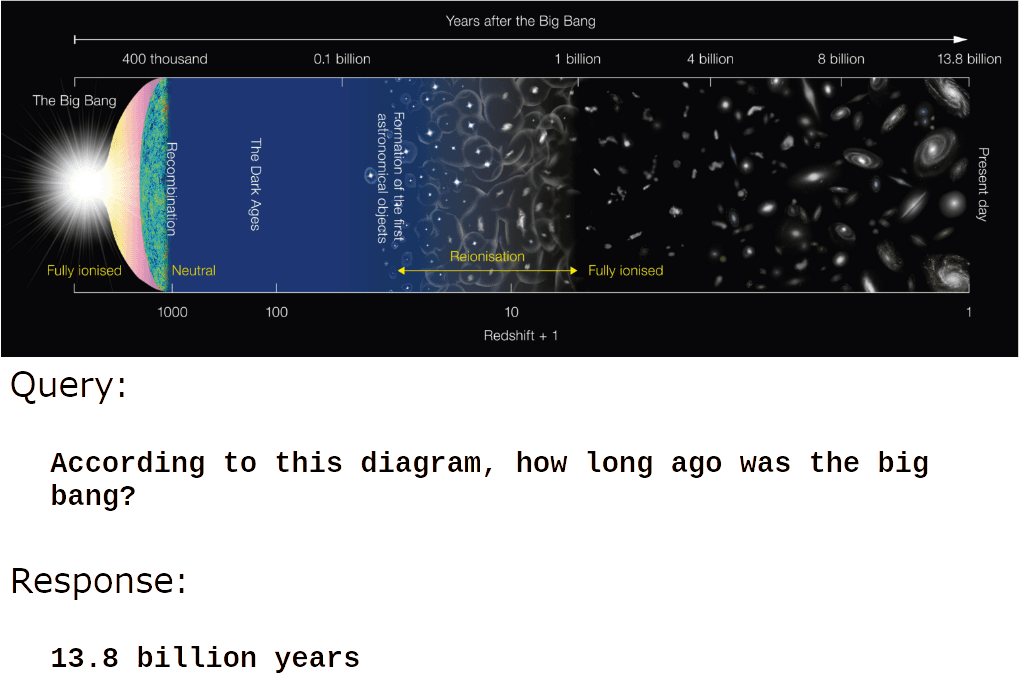

But where jina-vlm really excels is understanding the content of informational and man-made images:

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Or:

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

jina-vlm is well suited for automatic caption generation, product descriptions, image alt text, and accessibility applications for vision-impaired people. It also creates possibilities for retrieval‑augmented generation (RAG) systems to use visual information and for AI agents to process images without human assistance.