WARNING: This documentation covers Elasticsearch 2.x. The 2.x versions of Elasticsearch have passed their EOL dates. If you are running a 2.x version, we strongly advise you to upgrade.

This documentation is no longer maintained and may be removed. For the latest information, see the current Elasticsearch documentation.

Dealing with Conflicts

editDealing with Conflicts

editWhen updating a document with the index API, we read the original document,

make our changes, and then reindex the whole document in one go. The most recent

indexing request wins: whichever document was indexed last is the one stored

in Elasticsearch. If somebody else had changed the document in the meantime,

their changes would be lost.

Many times, this is not a problem. Perhaps our main data store is a relational database, and we just copy the data into Elasticsearch to make it searchable. Perhaps there is little chance of two people changing the same document at the same time. Or perhaps it doesn’t really matter to our business if we lose changes occasionally.

But sometimes losing a change is very important. Imagine that we’re using Elasticsearch to store the number of widgets that we have in stock in our online store. Every time that we sell a widget, we decrement the stock count in Elasticsearch.

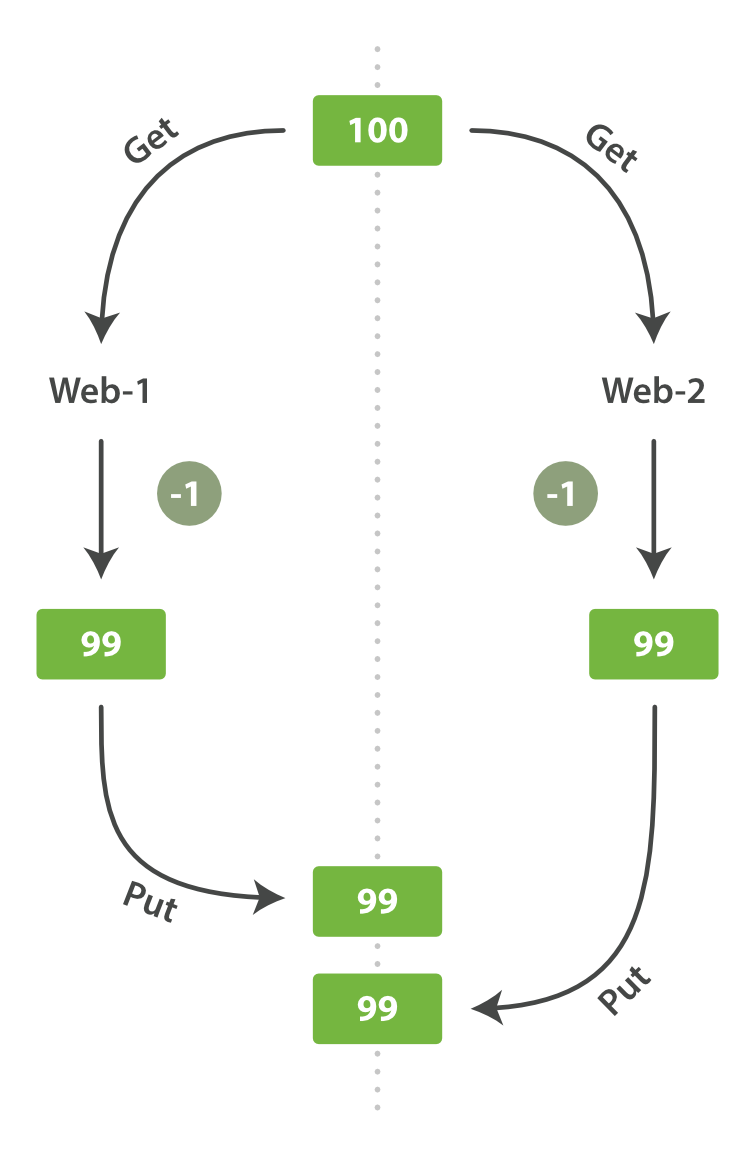

One day, management decides to have a sale. Suddenly, we are selling several widgets every second. Imagine two web processes, running in parallel, both processing the sale of one widget each, as shown in Figure 7, “Consequence of no concurrency control”.

The change that web_1 made to the stock_count has been lost because

web_2 is unaware that its copy of the stock_count is out-of-date. The

result is that we think we have more widgets than we actually do, and we’re

going to disappoint customers by selling them stock that doesn’t exist.

The more frequently that changes are made, or the longer the gap between reading data and updating it, the more likely it is that we will lose changes.

In the database world, two approaches are commonly used to ensure that changes are not lost when making concurrent updates:

- Pessimistic concurrency control

- Widely used by relational databases, this approach assumes that conflicting changes are likely to happen and so blocks access to a resource in order to prevent conflicts. A typical example is locking a row before reading its data, ensuring that only the thread that placed the lock is able to make changes to the data in that row.

- Optimistic concurrency control

- Used by Elasticsearch, this approach assumes that conflicts are unlikely to happen and doesn’t block operations from being attempted. However, if the underlying data has been modified between reading and writing, the update will fail. It is then up to the application to decide how it should resolve the conflict. For instance, it could reattempt the update, using the fresh data, or it could report the situation to the user.